Before we begin: here is the link to my GitHub page containing the extractor script I’ll be discussing below. This script automates the process of extracting and organizing an HTRC corpus, turning the compressed archive of page files into a collection of assembled full text volumes.

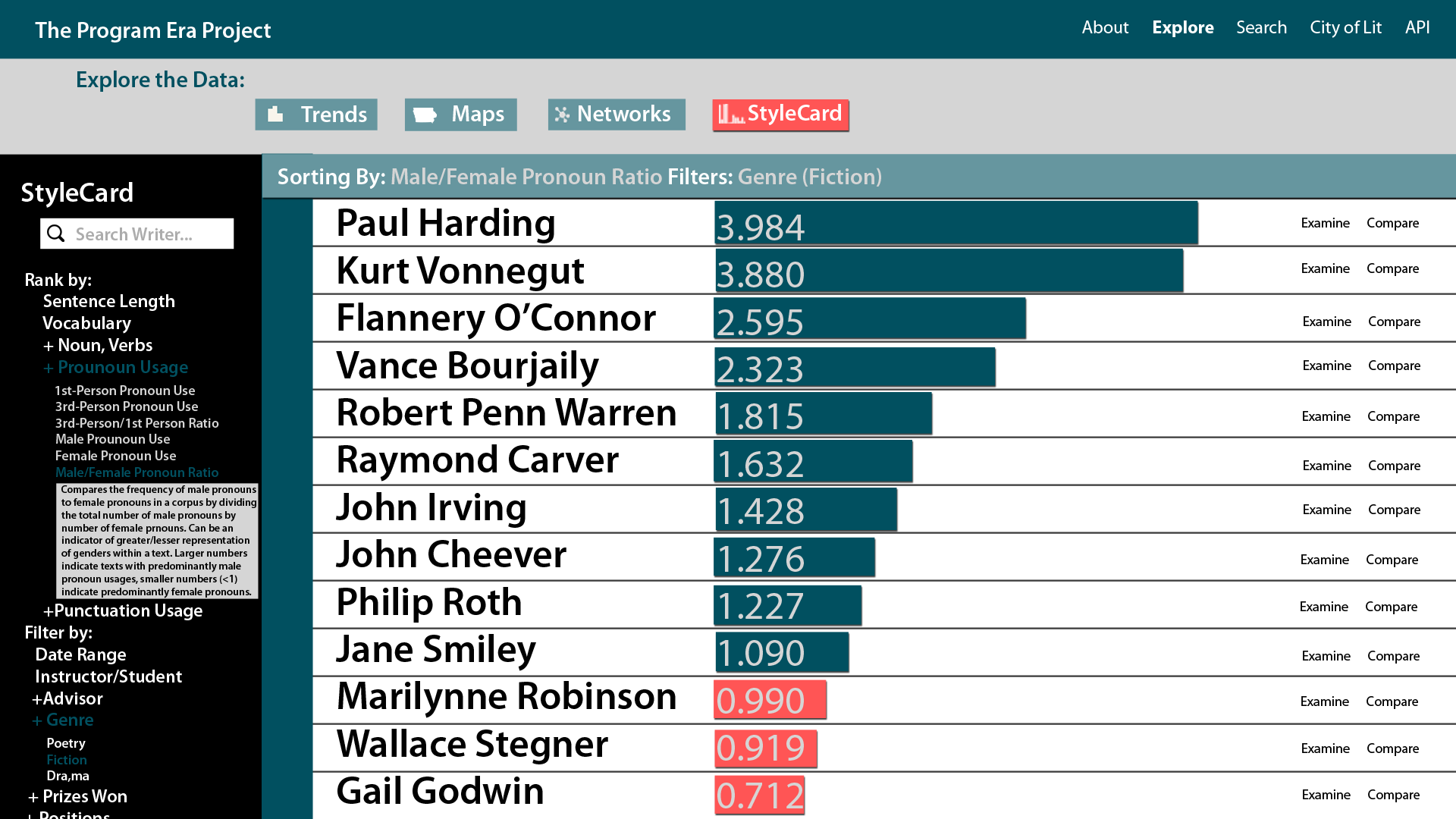

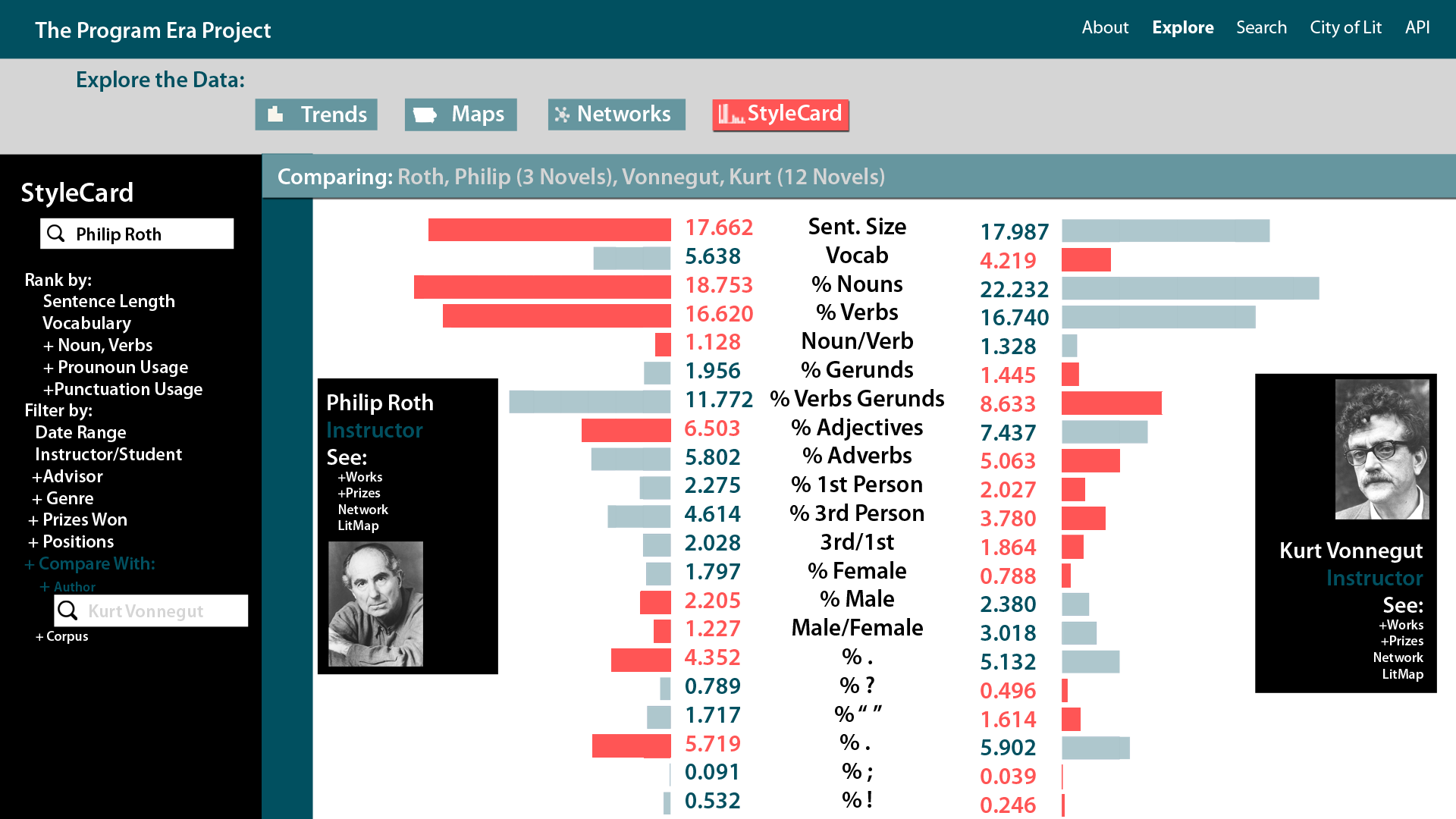

This post follows on the heels of the recent announcement that HathiTrust Research Center has expanded access to its collection of digital texts, making its complete 16-million-item corpus available for computational text analysis work. Given the challenges scholars can face with gaining access to digital texts—particularly texts under copyright—this is exciting news for computational literary scholarship. The Program Era Project’s own efforts to conduct computational text analysis on contemporary literature were only made possible through an earlier collaboration with HTRC, as I have discussed before.

Given that the scope of who can gain access to HTRC texts has greatly expanded, I wanted to offer an overview of the process I went through to prepare the Program Era Project’s HTRC corpus for text analysis. Hopefully, my walkthrough of how I extracted and organized our corpus offer some ideas or assistance to future HTRC users.

Moreover, I’ll also tell you about a tool I built that automates this extraction process, one which is now freely available on my GitHub. This tool can also be used in conjunction with other python-based text analysis scripts to automate the process of collecting text data from multiple volumes at once. In a moment, I’ll go into greater detail on how to use the tool and how to pair it with your own text analysis scripts. First, however, let’s see what the process of extracting and organizing a HathiTrust corpus looks like.

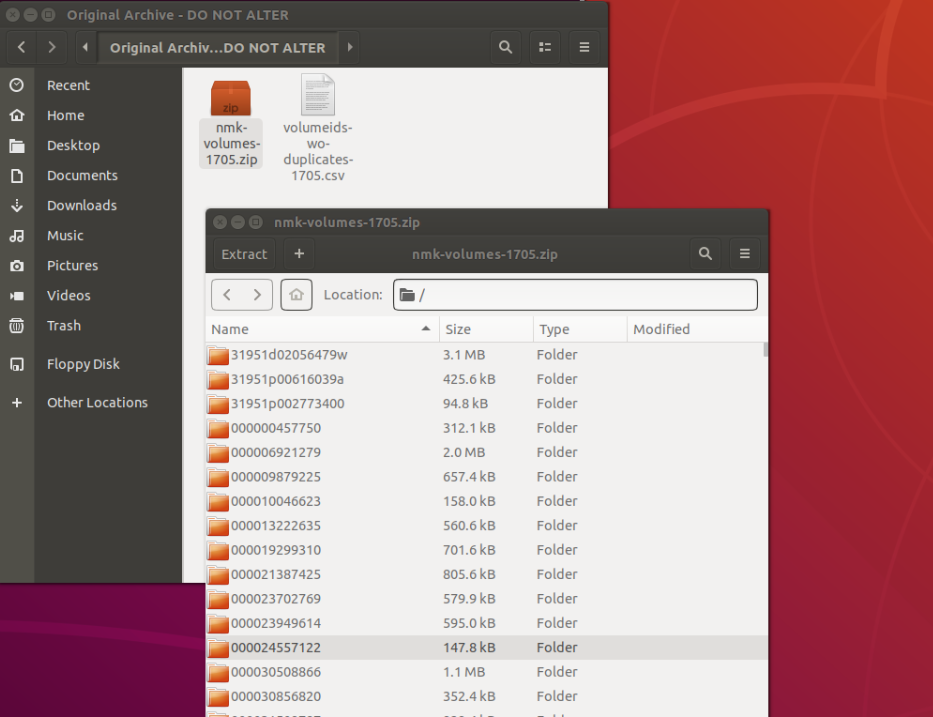

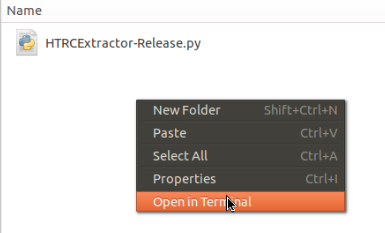

Figure 1: The Original Archive and its Contents

In this image, you see the initial archive we received from HTRC, a list of volumes and a compressed file which contains a series of folders. Each folder contains additional files, which will be accessible and useful to us as soon as we extract the initial compressed archive.

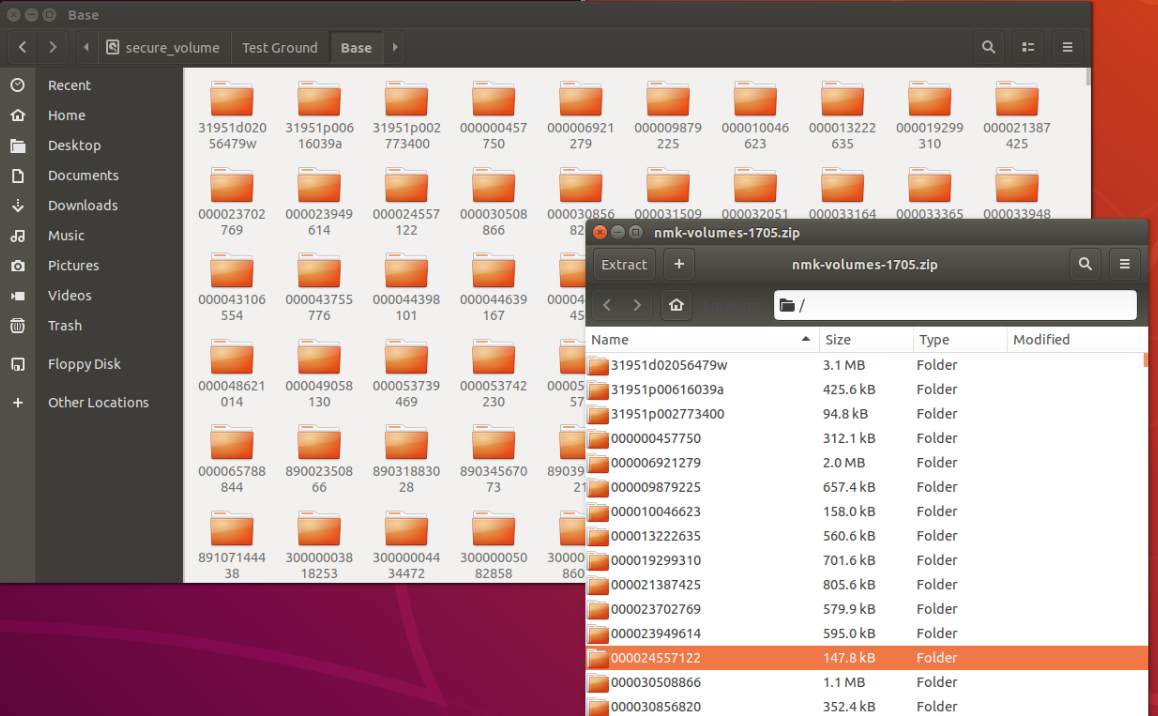

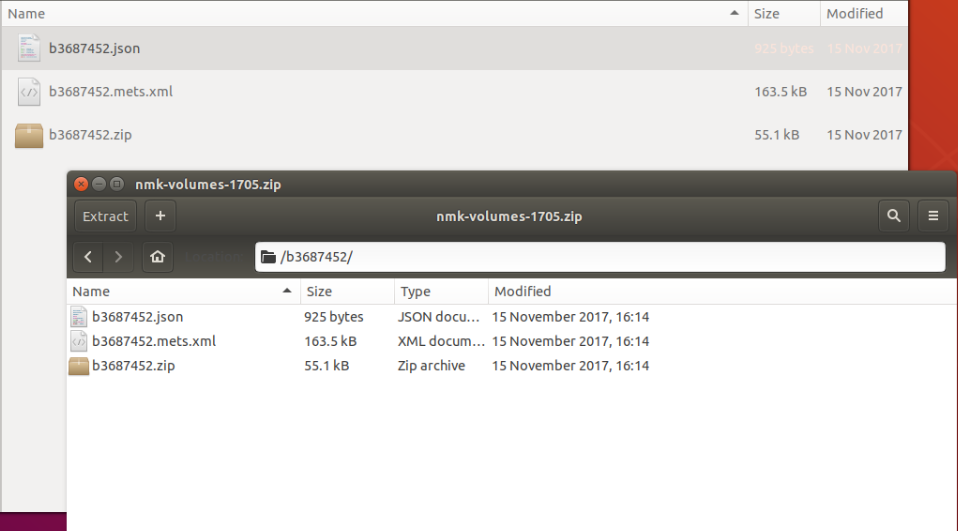

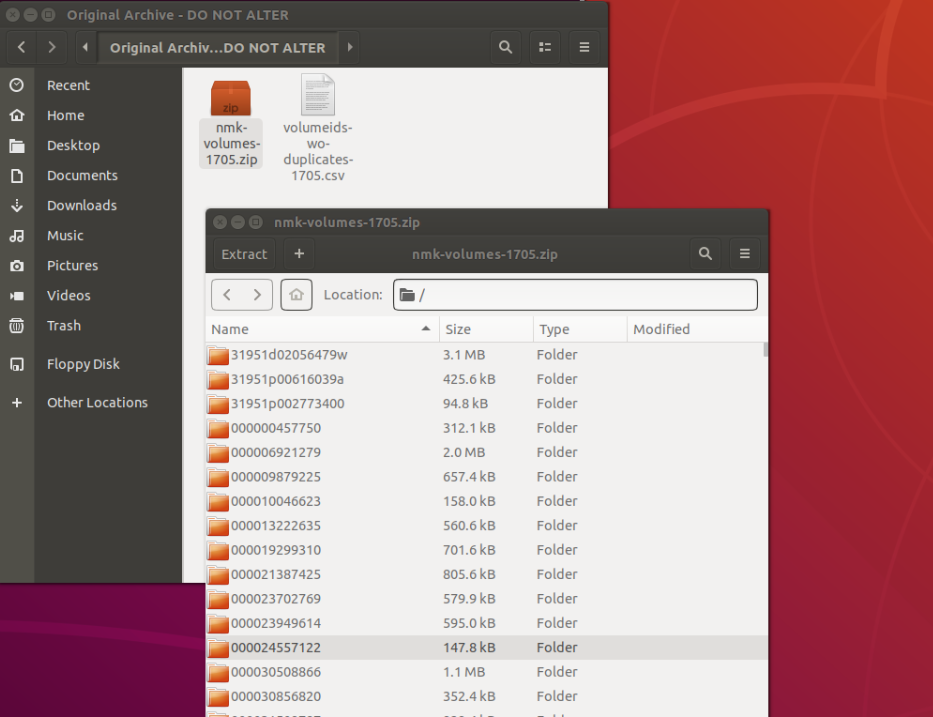

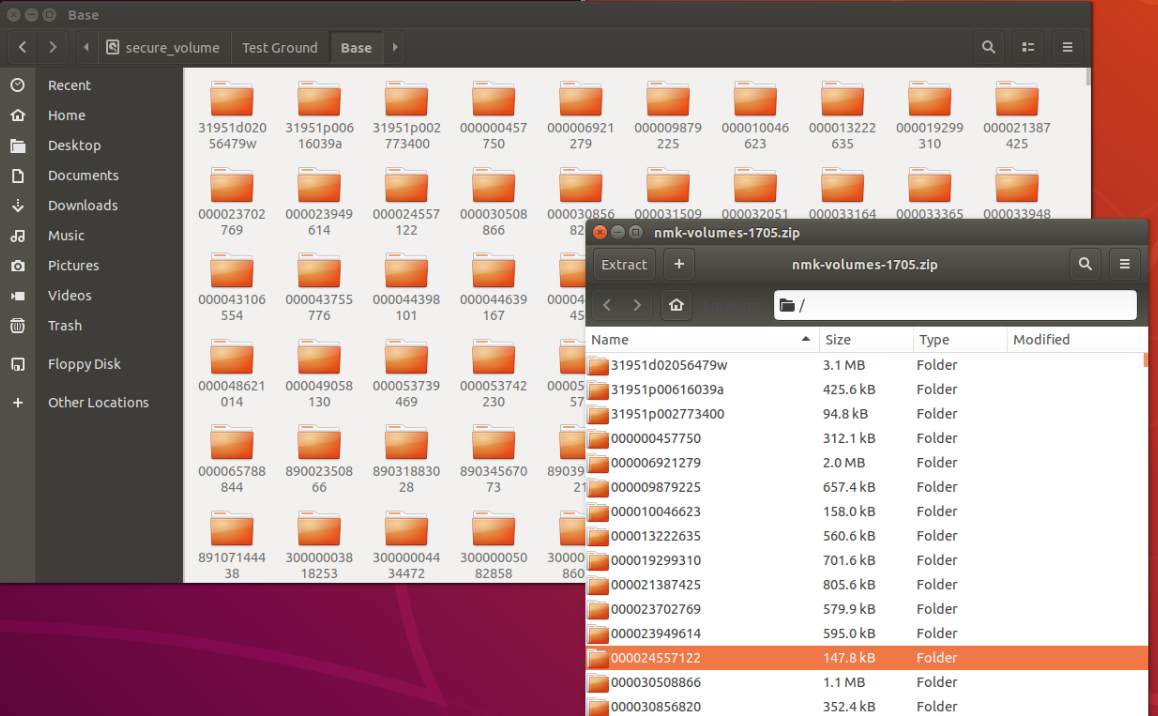

Figure 2: The Original File, Extracted

Figure 3: An Individual Folder in the Extracted Archive

The above image shows a folder containing the contents of the extracted file, each volume contained in a separate folder. The second image shows contents of a single volume folder. In each volume folder, we find a ZIP file containing the full text of our volume and a JSON file which contains metadata on the volume in question. There are important things to note about both the ZIP and JSON files, things which will impact how we extract and organize full texts.

First, it’s important to recognize that within each ZIP file the full text for a volume is not collected together as a single document. Instead, each page of a full text is included as a separate .txt file. We need to reassemble these pages to turn our volumes’ pages into a complete work.

Second, the JSON file provides a great deal of information on the text in question, information we can use for research purposes and to help organize our texts. Included in the JSON files are things like author names, book titles, and unique HTRC ID numbers for each book. These will be useful for automatically naming and placing files with our extractor tool. The JSON files also often (though not always) contain information like ISBN numbers, publisher names, and publication dates. The PEP team was particularly excited to discover this metadata, as it was information we could incorporate into our database of text metrics. This new information also enabled new ways to look at text data. Publication dates, for instance, make it possible to view trends in text metrics we’ve measured over time.

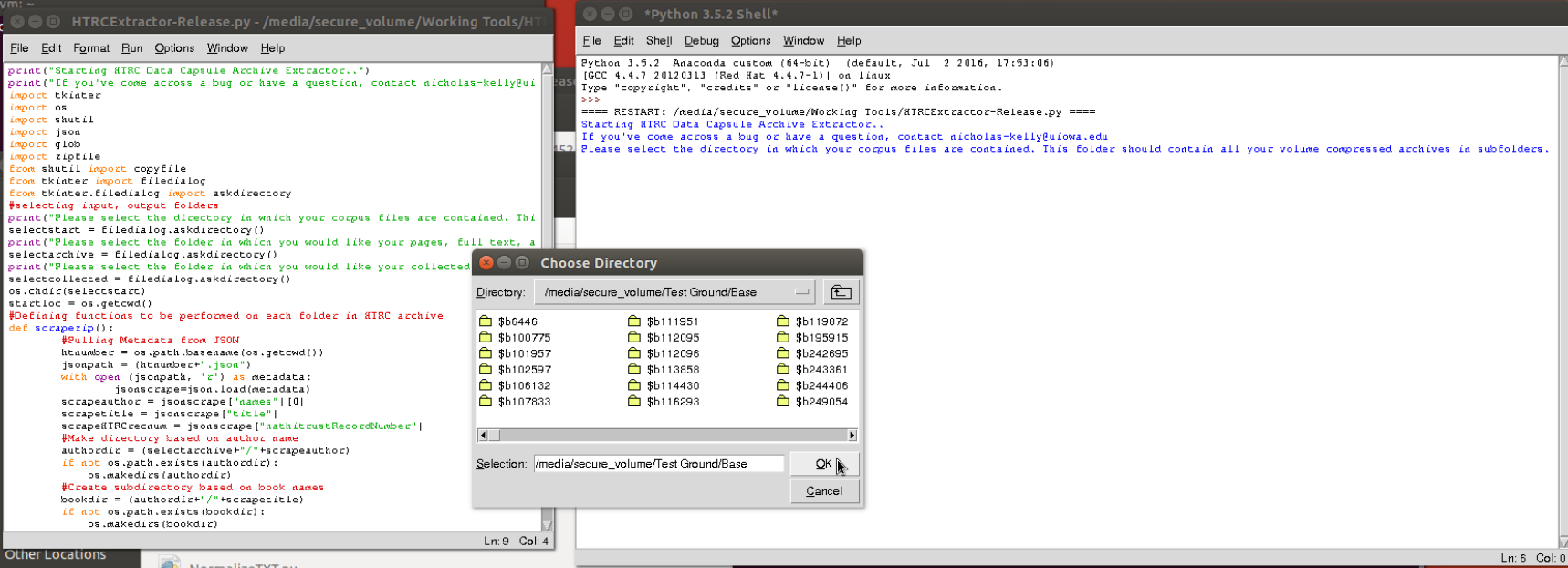

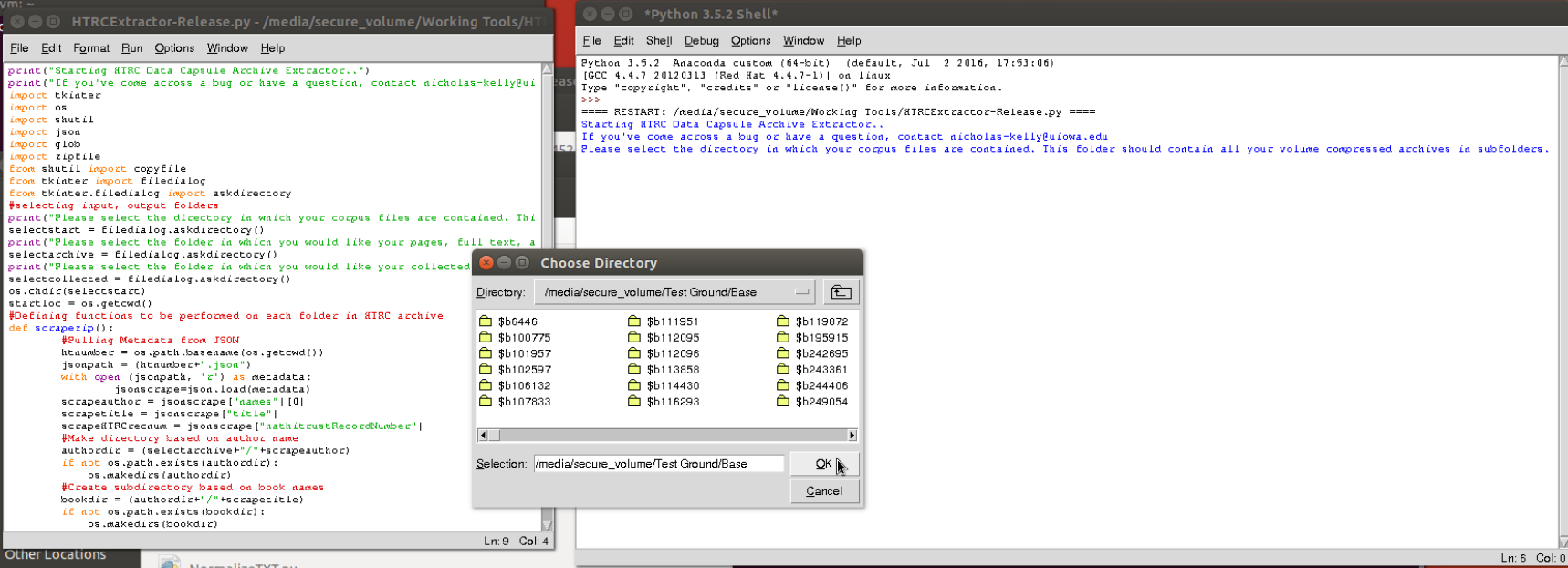

Figure 4: PEP’s Extractor Tool Running on an HTRC Corpus

The above image shows my Program Era Project extractor tool working on our HTRC corpus. It uses the metadata in the JSON to automatically organize volumes by author and title. It also extracts, sorts, and assembles the individual pages in each ZIP into a complete work. While the tech-minded are more than welcome to look directly at the tool’s code, in basic terms, the steps to turn an individual volume’s compressed files into a readable work looks like this:

- The tool pulls author name, work name, and HathiTrust ID data from the associated JSON.

- It uses the author name to create a folder for that author’s name (if one doesn’t already exist).

- It creates a sub folder within the author folder named after the volume’s title.

- It opens the ZIP file and extracts all page files to the book folder.

- It sorts the page files in numerical order and creates a single text file out of them, named “full.txt,” in the book folder.

- It places a copy of the metadata file in the folder, renamed with the HTRC ID number (e. a volume with the HTRC ID 123456 would be 123456JSON)

This gives us a single folder where all the volumes, their page files, and their associated metadata can be found. It is a catch-all repository for our HTRC corpus, which is now extracted and assembled as full texts. That said, this archive be somewhat large and unwieldy if all we’re interested in is the text files themselves, particularly in cases where the metadata might not be consistent. Discrepancies in author names, for instance, can create multiple folders for a single author, an issue that can been seen in the image below and can lead to data cleaning efforts.

Luckily, our tool gathers full texts together in another way. After the pages for a volume are organized and reassembled, a copy of the full text is placed in a folder set to be a complete repository of the full texts. In this folder (I call it “collected” above), each volume is named after its HTRC ID number. For example, a volume with the HTRC ID 7891011 would be 7891011.txt. This gives us a place where we have quick access to all our text files, and each is uniquely, consistently identified.

At this point, the extractor tool has done its work. However, we took a few additional steps to organize our collection and make it easier to navigate. Looking through the list of works provided by HTRC, the PEP team found a number of false positives, works not written by workshop authors that had been inadvertently included. We wanted to remove these authors from our list. We also wanted to find a way to relabel files in our collected folder to make it easier to find specific volume or a specific author’s works.

We turned to the HTRC ID numbers to help us remove false positives and rename the files for easy navigation. The PEP team created a spreadsheet of all the volumes in our collection. On this spreadsheet, authors name entries were made consistent and all false positives removed. Each volume entry also listed the title’s HTRC ID. Because we had the unique HTRC ID, I was able to build a script that searched for that unique identifier in each file name and automatically replaced that HTRC ID name with a new naming scheme (authorname+year). Below you can see our collected archive before and immediately after I have run the script.

Using these unique HTRC IDs allowed us a way to automatically replace enter clean, consistent data for our file names. As an added benefit, it made finding and removing all false positives simple. Because the false positives are not included in our spreadsheet, their names were not corrected. Therefore, any file that retained its HTRC ID was not on our master list and should be removed from our archive.

At this point, the PEP corpus had gone from a single compressed file to a collection of over 1000 full text volumes, assembled from individual pages, organized, and ready for future work. In the particular case of the Program Era Project, I incorporated our text mining scripts into the extraction process, producing datasets for each volume we could gather together into a larger dataset (after removing false positives).

Hopefully this account gives readers curious about working with a HTRC corpus a clearer picture of what to do to get a HTRC corpus organized and readable. However, as I said at the beginning of this post, I’m also happy to note that my github page contains a freely-available version of the extractor script I built to automation the extraction process.

The tool is designed to be as user intuitive as possible. No programming knowledge should be required, and the interface is almost entirely point and click. I’lll go through the steps to run the script here, but you can also find the readme for the extractor script on my GitHub.

To begin using the tool, your first step is to extract the initial compressed archive provided by HTRC. This should give you a collection of folders, each containing a ZIP file and JSON file. If you find a folder without a zip or JSON file, remove it. It will crash the tool. If, during extraction, you find a folder crashing your tool, check it for a missing ZIP or JSON.

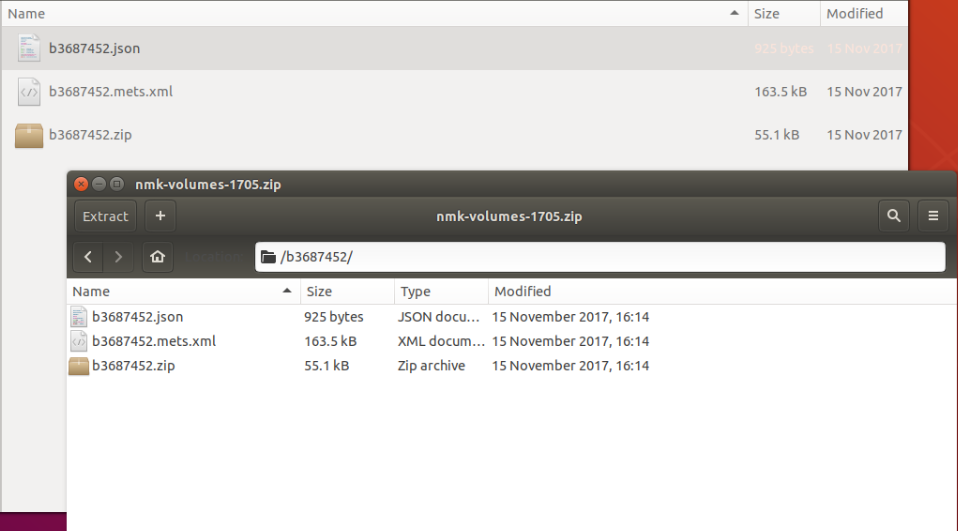

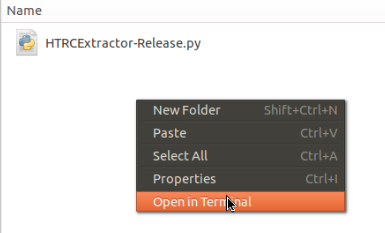

Figure 5: Opening the terminal

Once the initial archive is extracted, run the script. A simple way to do it can be seen above. First, right click somewhere in the folder where the script is located and select “open in terminal.” You can also navigate to the folder manually if you prefer. After you have done that, type in the following command:

python3 HTRCExtractor-Release.py

At this point, prompts will appear on the screen. They will ask you to select three folders:

- The first folder you select is the one which contains the subfolders with ZIP and JSON files.

- The second folder is where the tool will place all the page files, metadata files, and full text files, organized by author folders and work name subfolders.

- The third folder is the tool will place all the full text files (labeled by HTRC ID).

The tool should then run, letting you know as it works through the files in your archive. It will also notify you when it has completed. It lists my e-mail address should you encounter any bugs or have any questions, comments, etc…

Note: If you are working with the tool for the first time in a HTRC data capsule, you will want to run it first in maintenance mode, so that it can import any modules it needs to run. Once the initial folder select prompt appears, you can simply close the tool. You can then switch to secure mode and run the tool as I explain above.

For users who’d like to integrate their own text mining scripts into the tool, please examine the code. I’ve marked a place that allows you to insert your own scripts easily, running them on each volume you extract. Inserting text mining scripts there also allows you access to the HTRC metadata for the volume. I’ve also included some sample code to get the assembled file up and running for text-mining, though you may likely have alternative ways you’d like to work with or open the data.

To those of you interested in getting started with HTRC corpora, I hope this walkthrough and the tool provide some useful starting points. The more we increase the accessibility of computational text analysis tools and corpora (particularly corpora still in copyright) the more we all stand to benefit from greater diversity of computational analysis research projects as well as more experimentation (and, ideally, innovation) within the field of computational text analysis.

Happy mining.

![updated snip[1]](https://dsps.lib.uiowa.edu/programera/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2016/06/updated-snip1-300x107.png)