15th Annual Presidential Lecture Series

https://doi.org/10.17077/391t-sc3p

What Do We Represent?

Walt Whitman, Representative Democracy and Democratic Representation

F. Wendell Miller Distinguished Professor,

Department of English

University of Iowa

Introduction

The program opened with Professor Uriel Tsachor's performance of “So Long!” from Robert Strassburg's “A Whitman Trilogy.” Strassburg, a Los Angeles-based composer, teacher, conductor, pianist, and poet who has studied with Stravinsky and Hindemith, has also written a nine-movement choral symphony based on Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, more than 30 settings of Whitman’s poetry, and an opera, Congo Square, based on Whitman’s sojourn in New Orleans, for which he is currently completing the orchestration.

Writers’ Workshop professor Jorie Graham, the 1991 Presidential Lecturer, read passages from Whitman’s “So Long!” and “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” followed by President Mary Sue Coleman’s introduction of the speaker.

Jorie Graham reads from “So Long”

From “So Long!”

My songs cease, I abandon them,

From behind the screen where I hid I advance personally solely to you.

Camerado, this is no book,

Who touches this touches a man,

(Is it night? are we here together alone?)

It is I you hold and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms—decease calls me forth.

O how your fingers drowse me,

Your breath falls around me like dew, your pulse lulls the tympans of my ears,

I feel immerged from head to foot,

Delicious, enough.

...

Dear friend whoever you are take this kiss,

I give it especially to you, do not forget me,

I feel like one who has done work for the day to retire awhile,

I receive now again of my many translations, from my avataras ascending, while others doubtless await me,

An unknown sphere more real than I dream'd, more direct, darts awakening rays about me, So long!

Remember my words, I may again return,

I love you, I depart from materials,

I am as one disembodied, triumphant, dead.

Jorie Graham reads from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”

From “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”

Closer yet I approach you,

What thought you have of me now, I had as much of you—I laid in my stores in advance,

I consider'd long and seriously of you before you were born.

Who was to know what should come home to me?

Who knows but I am enjoying this?

Who knows, for all the distance, but I am as good as looking at you now, for all you cannot see me?

...

What gods can exceed these that clasp me by the hand, and with voices I love call me promptly and loudly by my nighest name as I approach?

What is more subtle than this which ties me to the woman or man that looks in my face?

Which fuses me into you now, and pours my meaning into you?

We understand, then, do we not?

What I promis'd without mentioning it, have you not accepted?

What the study could not teach—what the preaching could not accomplish is accomplish'd, is it not?

What the push of reading could not start is started by me personally, is it not?

University of Iowa President Mary Sue Coleman introduces Ed Folosm

Speech

President Coleman, friends, colleagues:

Fifteen years ago, my colleague in the English Department, Sherman Paul, stood at this lectern in this hall to inaugurate this occasion. This hall is a much different place now than it was then. Now the stage extends out to the audience, and the floor is solid. That was not always the case. Many of you will remember the days when any event in this hall had an extra edge of excitement and suspense, because there was a gaping abyss—an open, deep, unfinished orchestra pit—standing between the audience and whoever was here on stage. That pit kept performers and audience literally on edge. Then, a few years ago, a large net was installed over the pit. The net was here until just recently, and, as I contemplated this talk, the thought of that safety net gave me comfort. When Sherman Paul spoke here in that first Presidential lecture, in the last year of Reagan’s first term, he spoke without a net, and without precedent. He and my other distinguished predecessors in this series together wove a safety net, creating a fifteen-year pattern out of the variety of c(h)ords that make up this university—from neurology and anthropology and law, to history and music and religion, to biochemistry and creative writing and psychiatry, to engineering and film, to astronomy and internal medicine. They demonstrated, year after year, that it is possible, imaginable, to write and deliver a lecture like this, to say something worth using a February Sunday afternoon for: they created the net of possibility, the net of viability. And now, fifteen years later, thanks to them, the abyss has become a solid floor, stable enough now, I trust, to absorb an occasional fall.

In 1984, Sherman Paul opened the first Presidential lecture with these words: “In a very real sense what I am going to say is the cry of its occasion…Our occasion is communal, evidence of our common life…” Sherman went on to note that President Freedman’s mandate for this occasion provided for a “convocation,” a word which, Sherman noted, meant in its root sense that we were being called together “in order that we might have our vocations together.” And then Sherman went on to say something I’ve never forgotten, in part because he said it so often, on so many occasions, in his classes, in his books, on our February walks home up the icy wind tunnel of the Washington Street hill—they were the words of his vocation, and so I want to invoke them again, fifteen years after he voiced them: “No one will deny the pertinence of this mandate nor remain unmoved by the words community and communication. They are kindred words belonging to the commune cluster, having communis in common. We have our communion, we truly do, when we communicate, when by speaking to each other in a common language we create a common world and constitute a public realm. We join hands by speaking and enter the round dance.”

But Sherman Paul was no sentimentalist about the ease and wonder of community. I still remember him most vividly on those walks to and from campus, braced against the winter winds, defining himself—in the words of one of the poets, William Carlos Williams, that he and I shared a love for—defining himself “against the weather,” in his resistance to the expected, the conventional, the easy, aware that culture and community was a continual renewal, a continual standing in the face of. Sherman was a believer in new beginnings, in our ability to remake ourselves, to, as Williams put it, “begin to begin again.” But he knew that new beginnings are never easy, that claiming a birthright for oneself is a lifelong vocation, that, as he said here fifteen years ago, “the beginning, the new possibility, is a leaping into life, and the risk, the need for courage, is enough to make one cry.”

So Sherman, in that first Presidential lecture, focused not on community so much as on what he called “the scandal, so to speak, of a community of scholars no longer able to communicate with each other.” He critiqued the very event he inaugurated—he was, after all, looking for the cry, not the lullaby, of the occasion—by talking of the proliferation of disciplines, each with its own language: “Is there any longer a common language,” he asked, “among the many languages that comprise the University? Even now, as I speak, am I being heard?” “Even within a single discipline,” he noted, “there are now many languages, … languages that have opened a discipline that needed to be opened but that nevertheless widen the gulf of communication.” Standing here now, looking over this safely covered pit which then had not even a net, I realize that Sherman Paul was keenly aware of the gulf he spoke across in February of 1984.

Sherman Paul died in 1995, and this occasion is a fitting place to say, in Whitman’s words, “So Long!” to this legendary figure in the field of American literature, who tracked over his career what he called the “green tradition,” an emerging conception of the self that, as he said that day, would push beyond the “ego-mind” to an “eco-mind,” from “anthropo- and homocentrism” to “geo- or Gaia-centrism.”

Since today I want to talk about representation, I wanted first to begin by re-presenting Sherman Paul, and in doing so, to emphasize one aspect of representation, perhaps its most mystical and magical quality: with a slight shift of emphasis, we can hear in the word its most miraculous claim: to re-PRESENT, to make present again, to bring something or someone absent into presence. That’s also why I asked Jorie Graham to read the passages that she just so powerfully voiced. Part of what I want to celebrate, or evoke, here today is the community that Sherman Paul worried we were losing, to try to suggest some ways that we still represent, against all odds, community. To make my point, I’m even willing to commit what all of you have no doubt already realized is the rhetorical suicide of presenting Jorie Graham and re-presenting Sherman Paul before presenting what I have to say: because my experience at this university has been one of communis, not always and not always easily, but ultimately quite magically when I think of the growing variety that we as a university community have represented. In 1992, the centennial of Whitman’s death, I organized an international conference here, and colleagues from around the university—in the library, in the School of Music, in the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, in the Writers Workshop—all became involved in helping me represent Whitman, re-PRESENT him. No one did it more effectively than Jorie, who read Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” in such a seductively new way that no one who heard it on that occasion has ever forgotten it or been able to read it again as it was before that moment. It was one of many, many moments I’ve been grateful for in this community. I have enormous respect for this university, especially for its imperfections and its strivings and its willingness to take risks. Our strategic plans are important, but I’m most grateful for our accidental and surprising successes, the innovative and often unforeseen things that make us distinctly Iowa rather than the imitative things that make us just like so many other places.

* * *

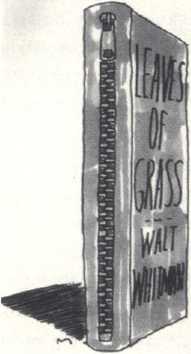

with zipper on spine

Well, a couple of weeks ago, I started getting the calls from reporters again. Once a year or so it happens: Walt Whitman, through some unimaginably circuitous route, makes his way back into popular culture, and reporters call to find out what his odd, stubborn reappearance means. Last year he cropped up in an episode of the television series “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman,” where he was openly portrayed as homosexual and where Dr. Quinn accepted rather than condemned his homosexuality. Various “family values” groups were outraged and felt betrayed by the episode, since such groups had until then considered “Dr. Quinn” a “safe” series. So the calls came; I even made an appearance on the Fox News “In Depth” program, facing the cameras to answer the suddenly burning media question, “Was Walt Whitman gay?” But a couple of weeks ago, that was no longer the question on reporters’ minds. President Clinton, so it was reported, had given Monica Lewinsky a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as a gift. “Can you tell me, Professor Folsom,” said the earnest USA Today reporter, “just exactly what Leaves of Grass represents?” “I’ve been preparing my whole career to answer precisely that question,” I responded, “but I doubt you really want my full answer.” I thought about inviting her to this lecture, but we both knew that by then, by now, it would no longer matter. Last week’s New Yorker featured on its last page a cartoon image of Leaves of Grass with a zipper on its spine. A newspaper in Buffalo quoted Section 5 of Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and asked readers if it didn’t sound a lot like oral sex, and wondered if this was why the President had given his intern the gift of Whitman’s words.

The past few weeks, then, have been another period in our nation’s history when the ideals of democratic representation and of representative democracy have both taken a hit. “What does the President of the United States represent?” and “What does Leaves of Grass represent?” both sound like significantly different questions today than they did at the beginning of the new year. In cartoons and commentary, both the President and Whitman’s book are represented by large zippers. It’s difficult not to hear, playing behind all of this, Whitman’s outrageous image of a continental sex act between the American poet and the North American continent, with the poet “incarnating this land, / Attracting it body and soul to himself, hanging on its neck with incomparable love, / Plunging his seminal muscle into its merits and demerits, / Making its cities, beginnings, events, diversities, wars, vocal in him.” Whitman gives a sexual edge to the “making of America” and reminds us that sex, America, and democracy are as deeply intertwined as…well, as “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” which is what most of us have been inundated with the past few weeks: what has been represented to us in our representative democracy.

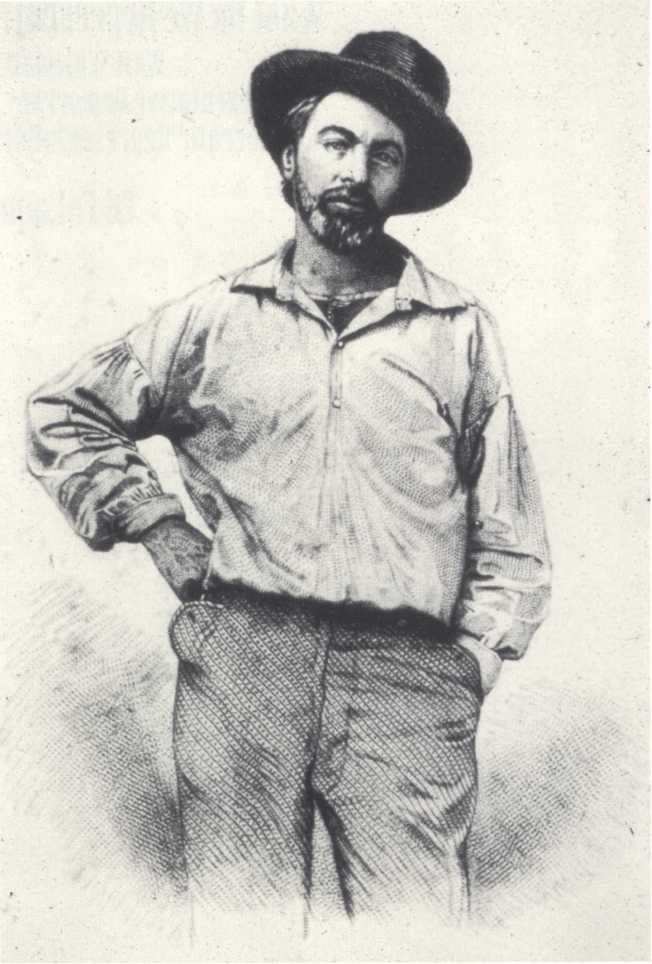

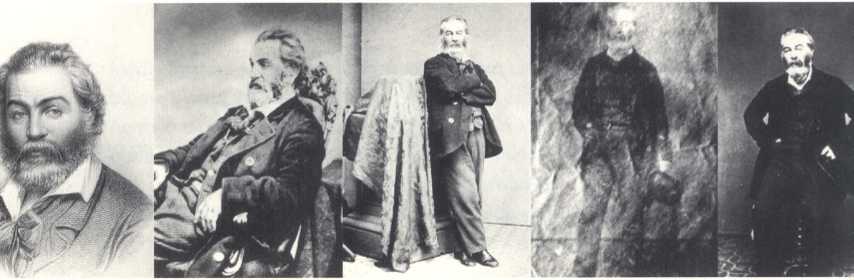

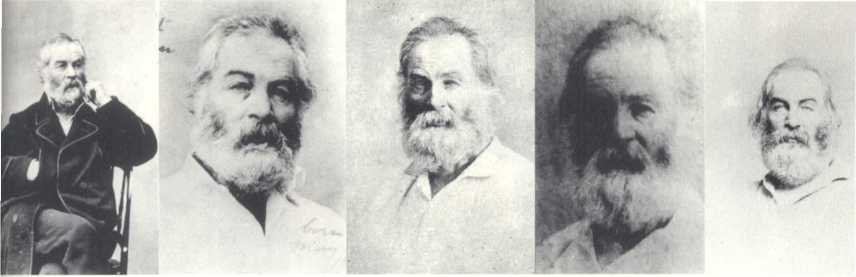

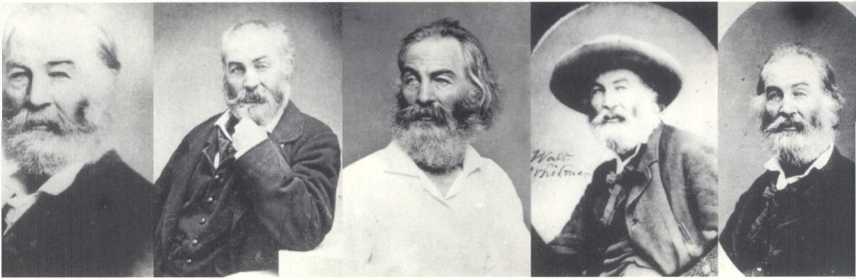

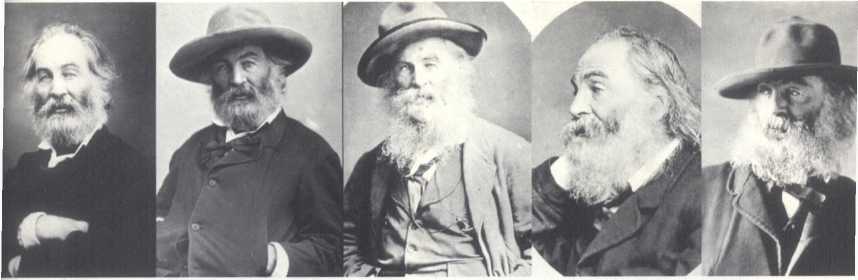

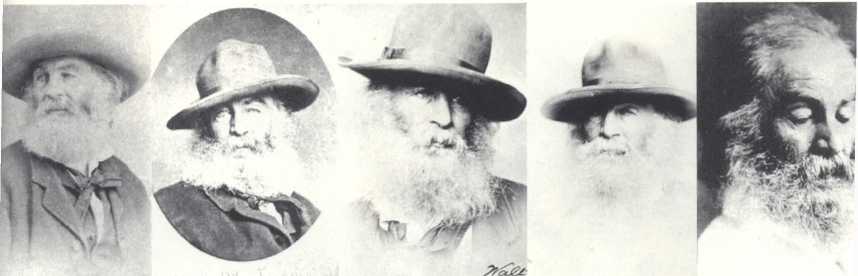

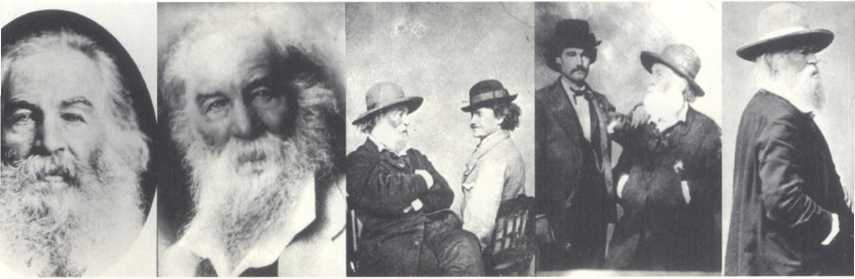

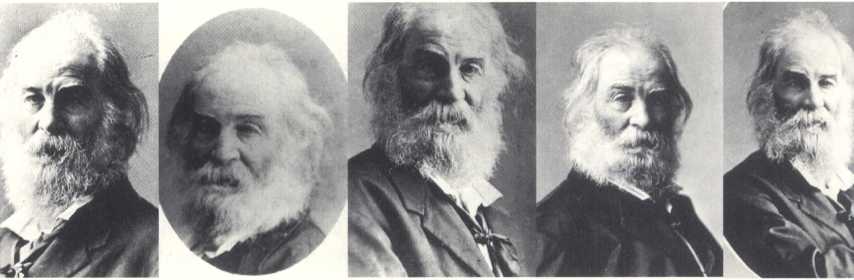

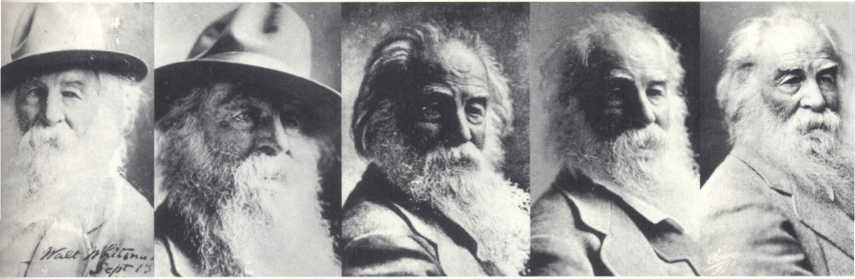

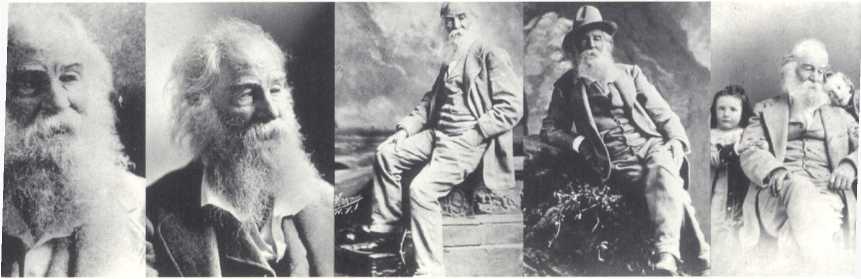

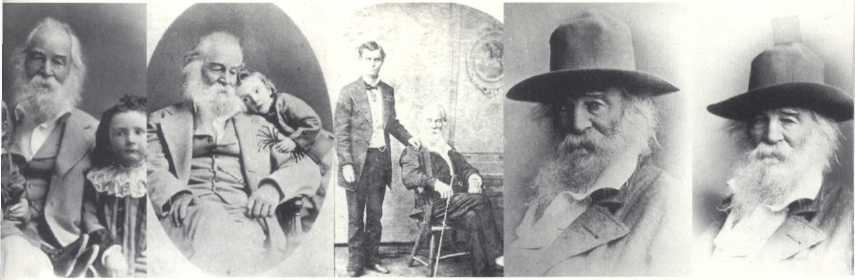

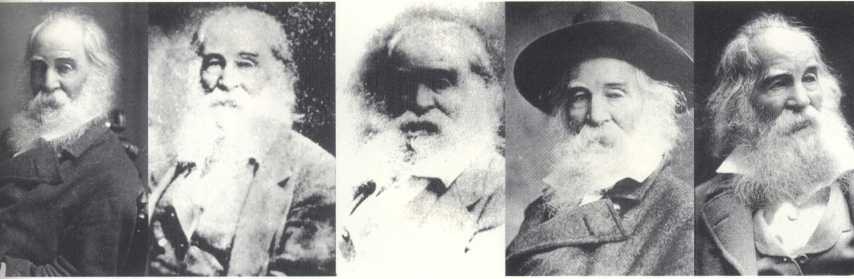

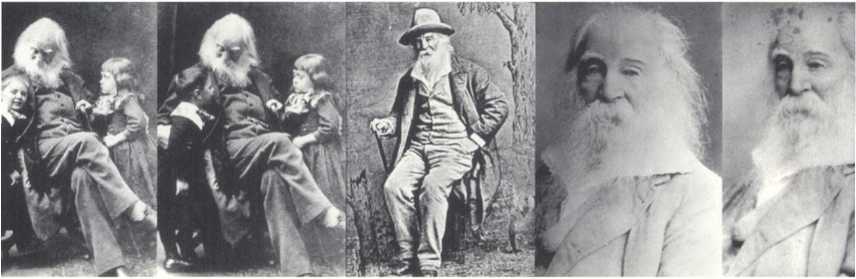

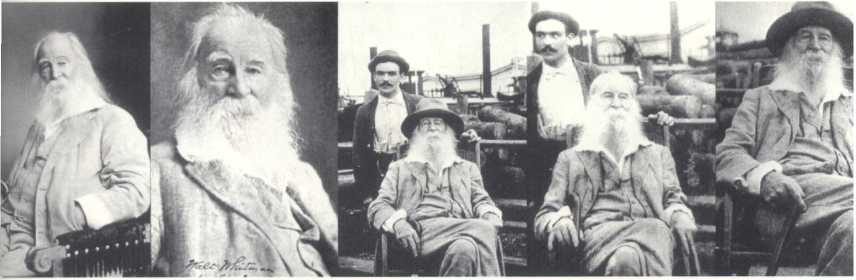

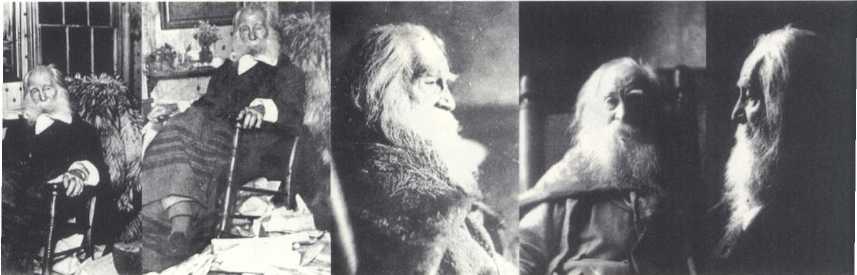

Right from the beginning, Whitman was obsessed with his physical self-representations and how they could build a democracy. A democracy, in practice, could only be built with bodies. When Leaves of Grass first appeared in 1855, Whitman left his name off the title page, but he used as his frontispiece an engraving of a daguerreotype of himself, one that was strikingly different than the usual representations of poets. It is the most influential portrait in the history of American poetry: a visit to the poetry section at Prairie Lights will confirm that it’s now virtually unthinkable to represent yourself as an American poet in formal dress and formal pose: the preferred dress is informal, wearing a hat is acceptable, being outside is nice, more than the head is essential. Whitman’s portrait was a polemic: this, it argued, represents the American poet: the poet’s name is not important (for he is representative—that would be the point of the poetry, to represent us each and every one), but the attitude is important: egalitarian, someone who works with the hands as well as the head, confident, poetry as labor instead of mental exercise, the poet not concerned with politeness (he’s either outdoors or contemptuous of removing his hat in order to be polite: in the preface to the 1855 Leaves, he said that part of the tone of the American poem was “ the President’s taking off his hat to [the common people] not they to him” ). It’s a poetry that emerges, Whitman’s portrait makes clear, not from the head and the intellect alone, but from the entire body, from a poet’s bodily experience in the world.

This portrait spoke volumes: it was a visual representation of the new, more comprehensive representation of the body and of previously unspeakable elements that Whitman knew a democratic poetry would need to bring to voice and to sight. So Whitman’s portrait is not centered on the head but rather on the torso—the site of appetite and desire. This is, for the first time, a poet with a zipper—or at least a button fly. Whitman once recalled how much controversy this portrait caused: “war was waged on it,” he said, “it passed through a great fire of criticism.” But he kept reprinting it, he said, “because it is natural, honest, easy: as spontaneous as you are, as I am, this instant, as we walk together.” It represented ease, spontaneity, physical desire, and it represented a new relationship between the poet and reader, as they walk together. This was poetry that you could dress down for; you weren’t going to be required to disguise yourself to read it, but rather—a more daunting challenge—you would need to “undrape” yourself. Whitman’s democracy begins with the body, because the place to begin to break down distinctions, he sensed, was in the frank recognition of the physical urges we all shared. Sexual desire, personal and idiosyncratic, resistant of social control, was the ur-force of democracy—“Urge and urge and urge, / Always the procreant urge of the world.”

Over the years, Leaves of Grass has represented many things, in many places. This past fall, I spoke about Whitman in Beijing, where there was palpable excitement about Whitman’s democratic notions, and where Whitman exerts a good deal of influence on a growing number of Chinese poets. I was able to spend an afternoon with Zhao Luorui, the translator of Leaves of Grass into Chinese; Professor Zhao died last month, but, when I spoke with her, she expressed gratitude to have lived to see her complete translation finally published and distributed: its publication had been suspended by Communist Party authorities in the wake of the Tiananmen Square democracy demonstration. Those authorities were afraid of what Leaves might represent at that moment to a significant number of new Chinese readers. Ai Qing, the great Chinese poet who visited the International Writing Program here at Iowa as one of the very first writers to be allowed to leave China after the Cultural Revolution, talked while he was here about how Whitman’s Leaves sustained him during his years in prison under the reign of the Gang of Four. Two years ago, when I taught in Germany, I encountered two distinctly different impressions about what Leaves represented. Whitman’s writings had been kept in print in both the former West Germany and the former East Germany, and, with the uneasy reunification of Germany has come a problematic reunification of two very different Whitmans: the neo-liberal democrat of the West and the socialist singer of the common man of the East. Behind both images stands the troubling memory that Whitman’s “Pioneers! O Pioneers!” had been used as a marching song for Nazi youth troops, at the same time that Thomas Mann’s reading of Leaves of Grass was strengthening his resistance of Nazism. In India and Nepal, on the other hand, Leaves represents a more spiritual kind of democracy, as Whitman’s poems are read as a kind of yoga discipline, a western version of Vedantic mysticism. Meanwhile, in Latin and South America, his poetry creates intense responses ranging from a spirited resistance to his perceived imperialistic Americanism through challenging revisions of his capitalistic-tinged, individualistic “I” into a more collectively inflected “we,” such as the Dominican poet Pedro Mir accomplishes in his “Countersong” to Whitman, “Song of Ourselves.”

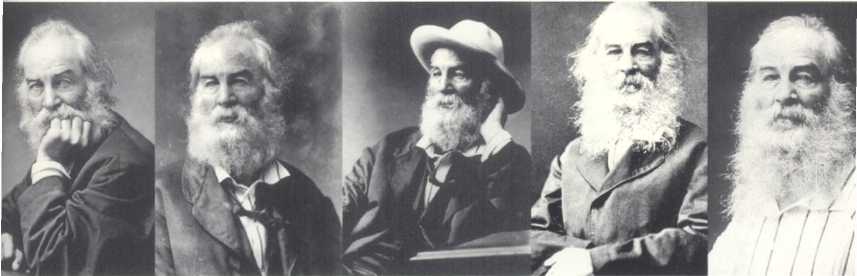

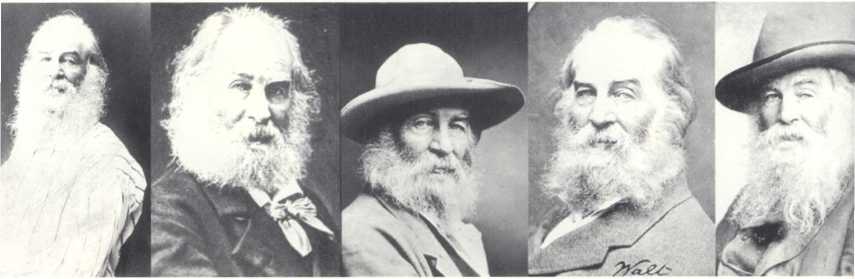

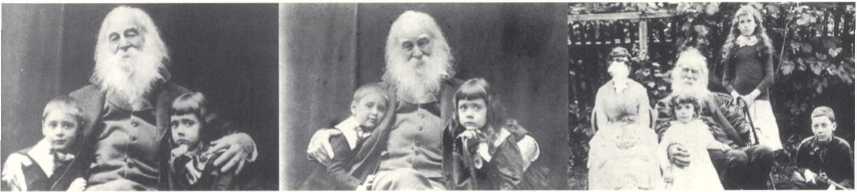

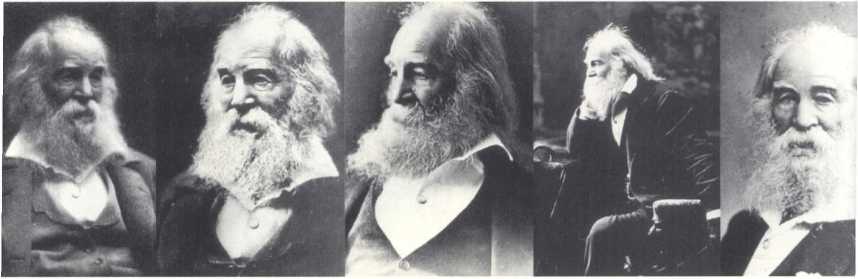

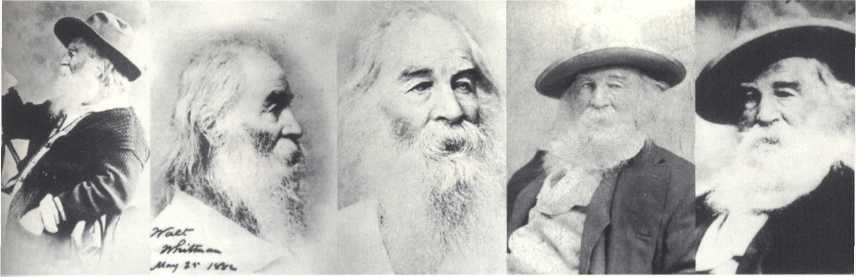

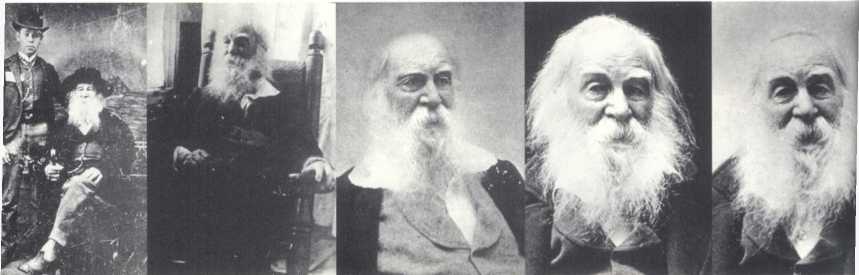

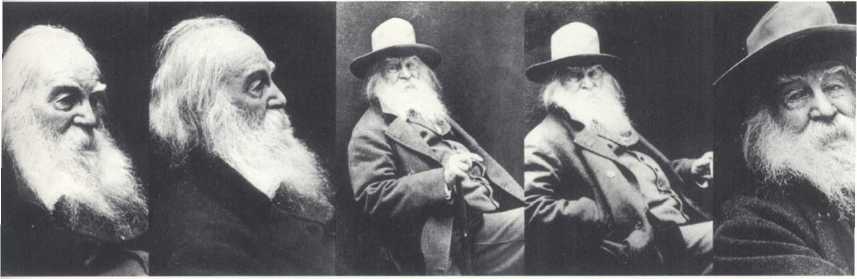

It would be tempting, if we had time enough, simply to focus today on these growing international encounters with Whitman. Once, when he was looking at the bewildering array of photographs of himself, Whitman said, “I meet new Walt Whitmans every day. There are a dozen of me afloat.” He would no doubt feel the same way were he able to see the versions of Walt Whitman that continue to emerge in cultures around the world: year after year in country after country, there are new Whitmans afloat. But today I’d like to turn us back to the United States, to some more local encounters with Whitman, and to Whitman’s more local encounters with us.

* * *

Whitman’s poem, “So Long!,” which you heard Jorie Graham read and which was the basis of the lovely piece Uriel Tsachor played, was written in the late 1850s, just before the Civil War began, when Whitman was about 40 years old. From then on, he printed it as the final poem in his forty-year book-in-progress, Leaves of Grass. One of the identifying marks of Whitman’s poetry—it’s part of how his poetry dresses down—is his use of colloquial American language in fresh and suggestive ways, as here when he appropriates as his concluding phrase the slang term for departure, the term he used with his ferry-boat and omnibus driver friends when they said goodbye to each other: So long. Not only does the phrase mean “good-bye,” but it carries the tonality of longing, of desire. It promises return—it won’ t be “so long” until we meet again—while it also suggests the possibility of extended separation—it will be “so long” until we see each other. And the phrase acts as a kind of gentle command to yearn, to desire: “So, long.” We long for the reunion not to be “so long” in coming. Whitman loved slang, which he called “the lawless germinal element, below all words and sentences, and behind all poetry” the quality that provides, he said, “a certain perennial rankness and protestantism in speech”: he loved to listen to how much was wrapped up in an informal throwaway phrase like “So long!”

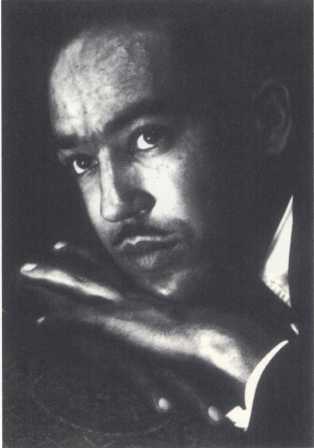

It’s easy to see why Langston Hughes, the great African-American poet, chose to echo this phrase in one of his earliest poems, “Afro-American Fragment,” written as he took a freighter to Africa for the first time, in the early 1920s, after dropping out of Columbia and tossing his books overboard as the ship entered the Atlantic, keeping only Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as his American companion for his journey to Africa, his journey to discover whether the fragmentation that he felt at the very hyphen of “Afro-American” could cohere into a single identity. His poem opens with the haunting words, “So long, / So far away / Is Africa.” He echoes Whitman’s “so long” as he says “so long” to America and embraces Africa, which is itself “so long” a journey and “so far away.” His desire for both Africa and America is intense, and Hughes’s forty-year wrestle with Whitman would lead him to the realization that—as he says in a later poem echoing Whitman—he, too, sings America: not only the white-man (or the Whit-man) could assume the voice of the culture, but so too could those writers identified as marginal—those writers who had waited “so long” to have their voices heard by the culture at large. “I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,” writes Whitman. “I, too, sing America,” answers Hughes a century later:

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

This kind of active engagement of Whitman by later writers, what I call “talking back to Whitman,” is one of the enduring fascinations of studying him—his work leads us to so many places, and to a multitude of voices, voices that argue with Whitman, agree with him, confirm and deny him, as they talk back to him in a double sense: speaking with him across time, as if he were still there to hear, to answer; and replying to him impertinently, with belligerence, like daughters and sons talking back to their poetic father, often a bit embarrassed by the old man, as they carve out their own identities. So another temptation today might be to trace out some of those charged dialogues between Whitman and what he called the American “poets to come,” the multitudes of poetic voices that have learned his most important lesson, that “He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher.” “Resist much, obey little,” Whitman counseled as the best behavior in a democracy, and generations of poets have followed that advice as they have resisted him while on another level obeying him (how can you resist much and obey little without doing both?). So African-American writers from Hughes and James Weldon Johnson and Jean Toomer to June Jordan and Yusef Komunyakaa have sustained a lively argument throughout the twentieth century with Whitman, as have a growing number of Asian American writers, including Garrett Hongo and Maxine Hong Kingston, as well as Native American writers like Simon Ortiz and Sherman Alexie, and a surprisingly large number of women writers, from Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Emma Goldman through Willa Cather and Meridel LeSueur, on up to contemporary poets like Jorie Graham, at the heart of whose book Materialism stand Whitman’s lines from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” that she read for us today: “Camerado, this is no book,” he writes in his book, “Who touches this touches a man, / (Is it night? Are we here together alone?) / It is I you hold and who holds you, / I spring from the pages into your arms…”

“No writer describes the act of reading so erotically,” says Malcolm Cowley of these lines. Whitman, says Allen Grossman, creates a “new genre exploratory of presence unmediated by representation.” Carroll Hollis says that “Whitman pulls the most successful metonymic trick in poetic history, “creating a “secular transubstantiation” of body into book: instead of “Take, eat, this is my body,” Whitman enjoins us to “Take, read, this is my body.” Whitman explored the erotics of the reading relationship more fully than anyone before him and most after him: “O how your fingers drowse me,” he says, as our fingers touch his words as we read; “your pulse lulls the tympans of my ears,” his words say as our wrists, resting on his page, ring with the rhythmic pulse of our blood. “Who touches this touches a man.” Whitman seems to be able to present himself—make himself present—where other writers could only represent themselves. We know he’s not really there, but we feel ourselves so intimately addressed in the very act of our reading that we have the uncanny sense that we are experiencing presence rather than re-presentation.

Whitman develops that uncanny sense of his presence not to make us experience him, but rather to make us experience ourselves, to make the act of reading yield an awareness of ourselves in the act of reading. Whitman was convinced that what America needed if it were to develop democratically is a change in its reading habits. He thus in effect invented reader-response criticism, demanding of readers response—active encounter, not passive acceptance. He called for an American literature written “on the assumption that the process of reading is not a half-sleep, but, in the highest sense, an exercise, a gymnast’s struggle; that the reader is to do something for himself, must be on the alert, must himself or herself construct indeed the poem, argument, history, metaphysical essay—the text furnishing the hints, the clue, the start or frame-work. Not the book needs so much to be the complete thing, but the reader of the book does. That were to make a nation of supple and athletic minds, well-train’d, intuitive, used to depend on themselves, and not on a few coteries of writers.

Or, as he says in one of his poems:

Doctrines, politics and civilization exurge from you,

Sculpture and monuments and any thing inscribed anywhere are tallied in you,

…

If you were not breathing and walking here, where would they all be?

The most renown’d poems would be ashes, orations and plays would be vacuums.

All architecture is what you do to it when you look upon it,

…

All music is what awakes from you when you are reminded by the instruments.

Whitman’s great realization, it seems to me, is that he could—through his words, at the moment we read them—call us into the presence of the poem, make us respond, make us aware of the physical act of reading, of the fact that reading is a physical act. Instead of representing a world elsewhere, then, he presents us to our own world; instead of taking us to other worlds and other times, he beckons us to this moment, now, the moment of encountering the poem, awakening the poem within ourselves, with our blood circulating, our eyes registering the reflected light of his words on this page, our lungs breathing this air:

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.

Instead of representing a world for a reader to look into, Whitman makes his reader the subject of his poems: the striking realization we have in reading much of Leaves of Grass is that we, at the moment of reading the poem, are what the poem has worked to call into presence. His poems are addressed to, in his own inimitable democratic phrase, “You, whoever you are.” Whitman wants his words to yield us, perpetually in the present moment: “I consider’d long and seriously of you before you were born,” he says. He knew that if he were to have any readers after he died, they would have to be alive, and in that relationship between a dead poet whose body was now his book (his body of work) and a living reader who would supply all the presence that was necessary—in that relationship was the possibility of magic, of reversing the expectations of the reading act, of making the reader the voice, the agent of the moment: to be the true subject of the poem meant that the reader would also, surprisingly, be the active agent of the poem, the only living actor who could bring it into being and generate its meaning. Perhaps it is no accident that Bram Stoker was a great fan of Whitman’s: something like a vampire, Whitman’s poems stalk the world, looking for the living to provide them blood. Without our blood, our breath, the poem can not be re-PRESENT-ed.

I realize now that it was many years ago I first sensed this quality in Whitman’s poetry. My first encounter with his work was in eleventh grade, in the late November of 1963, the day John Kennedy was assassinated. I was in a physics class when the shattering announcement came over the school’s PA system, and our physics teacher had barely paused before continuing with his explanation of vector sums. In my next class, my history teacher said only that there was nothing to say, which seemed a right thing to say, but not a very helpful one. Then, in my English class, my teacher (Tom Dunford), walked into the room five minutes late, an unprecedented tardiness, stood behind the small lectern on his desk, and opened a copy of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, a book we were to study later that year, and read, with no introduction or explanation, Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” his great poem written on the occasion of Lincoln’s assassination, then closed the book and left the room. I didn’t understand a word of what I had heard. But I also knew, somehow and somewhere, that those odd words which never mention the event or the person they are responding to (Lincoln and the assassination are absent from the very poem that responds to them) were the only words that I heard that day that seemed appropriate. But what did that poem represent? I didn’t know then, and I don’t know now: it has remained for me the one Whitman poem that is an absolute mystery. But those words seemed more concerned with manifesting me in a process of grieving that with representing grief. The poem was somehow calling my grief into presence.

Its opening lines, you’ll recall, represent a spring day, “When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom’d, /… I mourn’d, and yet shall mourn with ever-returning spring.” Only much later would I learn that Whitman was visiting his mother’s home in New York when he got the news of Lincoln’s death; he got up from the breakfast table, walked out into the dooryard, where lilacs were blooming that April day, and, gripped by grief, he inhaled deeply, and the scent of lilacs forever fused in his synesthetic memory with the news of Lincoln’s death, so that from that moment on, spring, the season of new beginnings, brought a sensory memory of death and grief, now bound permanently with birth and spring: “find myself always reminded of the great tragedy of that day,” he wrote, “by the sight and odor of these blossoms.” His aesthetic response to the tragedy was synesthetic, and that recycling affiliation of death and birth, grief-work and new beginnings, kept his response from ever becoming anesthetic. The smell of lilacs would always be the sniff of birth and the scent of death. And the poem required breath, a breathing reader, who would inhale air long after Whitman’s death and exhale grief. Whitman’s “Lilacs” were now, through the trick of metonymy, both flowers and poem, and the act of reading becomes, as it always is, a physical act of inhaling and exhaling. T. S. Eliot, sixty years later, working out his own troubled and complex relationship with Whitman, would echo him in the opening of his own shattered poem written in the aftermath of loss and grief following the First World War: “April is the cruelest month, breeding / Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing / Memory and desire…” Eliot in The Waste Land understood the cruelty of April because he understood the persistence of memory in the renewing cycles of life. “When Whitman speaks of the lilacs,” Eliot wrote in 1926, “his theories and beliefs drop away like a needless pretext.”

* * *

Well, I agree with Eliot on one level. But on another, I love Whitman’s theories and I’m fascinated with his beliefs. In fact, I’ve devoted a significant part of my career to his “needless pretexts.” Pre-texts—those theories and beliefs that consciously or unconsciously organize and structure a text—are of particular interest with Whitman, most of whose writing, it turns out, is pre-text—notes and drafts and versions of passages later discarded, absorbed, rearranged, melded. Henry James once said that “It takes a great deal of history to produce a little literature.” He was talking about Hawthorne and fiction, but I believe his insight applies even more to poetry, where, especially in American culture, historical, political, and artistic strands continually get entangled. Whitman’s pre-texts constitute a vast examination of our history in the service of producing a little literature. In the very origins of our nation, the diction of democracy—and its odd corollary, representation—is the lexicon out of which our government and our poems are constructed.

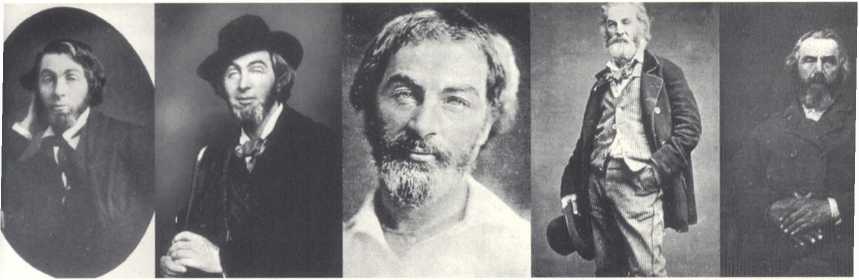

In this country, we have our House of Representatives, and in our literature we have our House of Representations, a house where the debate is increasingly as ideological and political as in the other, more ostensibly political representative house. Of late, authors have often come to seem, in the hands of some critics, little more than representatives of various political and social concerns, as their poems and novels are re-read as veiled political speeches. For Whitman, this confluence of political and artistic representation seemed natural—seemed, in fact, the very essence of a democratic poetics. He believed that America’s imaginative literature had to take up where its politics left off: when theories of representation began to fail politically, as they certainly did during the years leading up to the Civil War, then theories of imaginative representation were the only hope to save democracy. While I talk for a few minutes about Whitman’s notions of democratic representation, I will be flashing up on the screens a series of photographs of Whitman, which I’ve gathered over the years: for Whitman as for many Americans in mid-nineteenth-century America, photography was the great new technology of representation, and, as I’ll explain in a few minutes, it is no accident that Whitman’s notions of democratic representation developed precisely at the time photography was sweeping the country and altering the way Americans saw their world and themselves. Photography quickly became the cheap and easy art, the technique of representation that allowed people who had never had visual representations of themselves before to suddenly have multiple self-representations. It was the technology that threatened through its sudden ubiquity to soon turn everything and everyone—including our memories—into a photograph. As Susan Sontag has remarked, photography even led to a new definition of reality: something is real if it can be photographed. For Whitman, it was precisely what a country facing a crisis in representation needed: an endless new set of representations that did not discriminate on the basis of perceived worth or assumed hierarchical value, an absorptive new technology that did not divide and select but that absorbed and gave every detail its place. He wanted to create a poetry that would do precisely the same thing. By the mid-nineteenth century, photographs were widely and cheaply available, and the multitude of identities in America were gaining equal significance—representation was flattening out, as everyone began getting herself or himself accurately represented. Portraits were not just for the important people anymore—or, rather, democratic portraits were now beginning to make everyone important.

Meanwhile, our political House of Representatives seemed to be failing dramatically in its ability to represent the fullness and variety of American experience. The old anti-federalist nightmare about representative democracy had seemed to come true: these Representatives did not resemble and had become distant from those they represented. As one anti-federalist put it back during the Constitutional debates, “The very term representative, implies, that the person or body chosen for this purpose, should resemble those who appoint them—a representative of the people of America, if it be a true one, must be like the people … They are the sign—the people are the thing signified.” Or, as John Adams warned in 1776: “the greatest care should be employed in constituting this representative assembly. It should be in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large. It should think, feel, reason and act like them.” A formative Constitutional anxiety in this nation, then, was the concern that our representatives would not be representative, that they would lack “likeness” and “closeness” to those they represented. Now, if we all close our eyes for a moment and picture our current House of Representatives—you all saw them at the State of the Union address—we can answer for ourselves whether what we have there is “in miniature an exact portrait of the people at large.”

For most of us today, the phrase “representative democracy” seems like a reasonable and self-evident label of how we conduct our public affairs—at the university, local, state, and national levels—even if at the very origins of this nation, the term seemed an oxymoron more than a commonplace. Representation was a huge gamble, many felt, that would lead not to the establishment of democracy but rather to the loss of democracy and to the institution of an elite group of rulers no different essentially from other forms of oligarchy. We need to recall that at America’s originating moment, the theories of representative government did not sit easily with the theories of democracy. It’s too late in the afternoon to begin quoting from the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers, but it’s important to remember that the nature of representation was a major issue, that it was not self-evident that a relatively small number of representatives elected by huge groups of voters would form anything resembling democracy. The history of this debate is part of the vast history that makes Whitman’s poems.

So it should probably not be surprising that Whitman wrote some of the very few poems we have that evoke the House of Representatives. We tend not to think of Newt Gingrich and our Representatives as natural poetic material, especially in a culture without an Alexander Pope, but Whitman wanted to explore the very grounds of democratic representation, so he often took a close look at the House of representative democracy. Political representation, in Whitman’s eyes and the eyes of many others in the years preceding the Civil War, had demonstrably failed. Whitman had taken to cataloguing political representatives—in one of his milder catalogs, he called “office-holders” and “office-seekers,” among other worse things, “infidels, disunionists, terrorists, mail-riflers, slave-catchers, pushers of slavery, creatures of the President, … spies, blowers, electioneerers, body-snatchers, bawlers, bribers, … crawling, serpentine men, the lousy combings and born freedom sellers of the earth.” “The cushions of the Presidency are nothing but filth and blood,” he wrote in the 1850s; “The pavements of Congress are also bloody.” “Don’t gauge us by the people that have gone from our parts to Washington,” he wrote; “We are live men. Stand back! We mean what we say.” His rage is related to Henry David Thoreau’s contempt for voting, which he saw as the surrendering of self, not the representing of self—“a will cannot be represented: it is either the same will or it is different,” Rousseau famously said, and Thoreau agreed: “The fate of the country,” Thoreau said, “does not depend on what kind of paper you drop into the ballot box once a year, but on what kind of man you drop from your chamber into the street every morning.” Whitman aimed to write poems that dropped readers into the street, that generated living people who would mean what they said: these were poems that would actively re-present Americans, not passively represent them.

Whitman, like many Americans, had become suspect of what was passing for representative democracy, and he began writing poems that called on Americans to resist being represented by anyone who spoke in a voice that did not re-present them and all Americans. He set for himself the goal of becoming that impossible representative voice, the voice that would in fact represent democracy—not parties or factions, but everyone in the nation. He set as his goal the creation of a voice fluid enough and expansive enough to inhabit the subjectivity of every single citizen in the nation. He began by jotting in an 1840s notebook his first surprising attempts at such a voice: “I am the poet of slaves and of the masters of slaves /… I go with the slaves of the earth equally with the masters / And I will stand between the masters and the slaves, / Entering into both so that both will understand me alike.” So begins Whitman’s representative poetic project, his poetics of “union,” a voice that would resist divisions and embody contradictions, not by rising above them but by inhabiting them. The poetry of democratic representation would ultimately succeed where the politics of representative democracy had failed, so Whitman believed, and it would work by becoming the most capacious representative, the voice that would speak for the full range of human possibility within the diverse culture, from slaves to masters of slaves. Such a representative voice would not initially or essentially be politically radical, but it would certainly be poetically radical as it developed a language that could absorb the most divisive issues in the culture, the full range of sociolects, and put the dissenting voices in conversation—within each of us.

What had to emerge in America, Whitman realized, was a whole new kind of representative mind, one that would accumulate instead of exclude, one that would join instead of separate, one that would absorb rather than discriminate. Thus Whitman began his call for an indiscriminate acceptance of diversity, as he became one of the first writers in English to sense the negative side of the process of discrimination: that any act of discrimination assured that someone or something had to be discriminated against. So, he believed, only by speaking for both slave and master of slave could the problem of slavery be overcome; political representatives were effectively speaking for one or the other, but no one was representing both and all between: only when a truly democratic identity became feasible—one in which everyone recognized himself or herself—would slavery be revealed as a failure of that identity. So Whitman developed his character of the new democratic American poet, the ultimate representative, the voice that would represent all of us by calling each of us into being and by convincing each of us that we were potentially everyone else. This would be the voice vast enough to speak the diversity of America, and it would issue a challenge to all of us to recognize our interrelationship with the culture, to see the range of human possibility in this country at any given time as the external manifestation of the range of human possibility that exists within each and every one of us.

And the proof would be in his readers, who would experience themselves called into being as that voice unlocked the indiscriminate imagination in each reader, broke down the walls of discrimination. “The proof of a poet,” Whitman bravely claimed, “is that his country absorbs him as affectionately as he has absorbed it.” Affection, the desire of imagination, the urge to join, would be how we would re-PRESENT ourselves to each other: “I speak the password primeval, I give the sign of democracy! / By God, I will accept nothing which all cannot have their counterpart of on the same terms.” We each have within ourselves the ability to represent everyone else, Whitman believed, because, given a democratic mind, we can ride the trajectory of our imaginations across barriers of race, class, gender. Until we hear that democratic voice and learn to speak with it, we are doomed to division and partial representation:

Every existence has its idiom, every thing has an idiom and

tongue,

He resolves all tongues into his own and bestows it upon men, and any man

translates, and any man translates himself also,

One part does not counteract another part, he is the joiner; he sees how they

join.

He says indifferently and alike How are you friend? to

the President at his levee,

And he says Good-day my brother, to Cudge that hoes in the sugar-field,

And both understand him and know that his speech is right.

He walks with perfect ease in the capitol,

He walks among the Congress, and one Representative says to another, Here is

our equal appearing and new.

It is a charged moment: the representative poet meeting the representative congressman, and the congressman suddenly recognizing the equalizing force of representation instead of its power to separate and factionalize. A representative coming to his senses: we know immediately we must be in a poem! But Whitman’s insistence that without democratic representation there cannot be representative democracy is worth thinking about: if we cannot imagine and develop a self that is democratically representative, how can a democracy ever work? Whitman, like most people, wasn’t sure it ever could; he knew he would never live to see it. His very definition of democracy cast the word always into the future: “Democracy,” he wrote, “is a word the real gist of which still sleeps, quite unawaken’d. … It is a great word, whose history, I suppose, remains unwritten, because that history has yet to be enacted.” But he went about the business of imagining what a democratic voice would sound like, what a voice that joined contradictions, that merged opposites would sound like “Do I contradict myself? / Very well, then, I contradict myself, / I am large, I contain multitudes” ).

Whitman set out to reverse our usual sense of the relationship between democracy and representation. Our political experience cast representation as the erasing of individual distinctions in elected representatives who acted on the behalf of the majority who elected them, but who were in no way obligated to be part of them or to be like them or to enact the identity that joined them. Whitman sought instead a much more difficult kind of representative function, to be representative of the roiling contradictory variety of the American population, majorities and minorities. Could there be a representative self large enough to contain it all, to contain the multitudes, to contain the vast differences of diversity without erasing the difference? Whitman’s answer was that there had to be such a self, and that that self actually slept in each of us. Its absence was nothing but … a failure of imagination. The democratic poet’s job was to awaken the sleeping democratic self in each of us, to break it out of its lethargy of discrimination and hierarchy and closed-mindedness. The end of slavery would come, Whitman believed, when the slave-owner and the slave could both be represented by the same voice, could both hear themselves present in the “you” of the democratic poet, when the slavemaster could experience the potential slave within himself, and the slave know the slavemaster within himself or herself, at which moment slavery would end. It didn’t end that way, of course: it ended in a very different, more divisive way, and because of that never really did end—but that’s another vast history that makes another set of poems to be talked about on another day

And what does all this have to do with these photographs you’ve been seeing today of Whitman, the most photographed writer of the nineteenth century? When Whitman saw the first daguerreotype studios in the 1840s, with their galleries of portraits of the famous and the unknown, he was convinced he had found the first democratic representation, the first mode of re-presenting that was metonymic, an actual part, a trace, of the person or scene it represented. “The photograph has this advantage,” he said; “it lets nature have its way: the botheration with the painters is that they don’t want to let nature have its way: they want to make nature let them have their way.” This is the key to what became Whitman’s unwavering devotion to photography; precisely because he believed it mechanically reproduced what the sun illuminated, it was for him a more honest re-presentation of reality than the paintings of most artists, who let their various biases, discriminations, and blindnesses alter the world that was before their eyes. As such, photography was the harbinger of a new democratic representation, an art that would not exclude on the basis of preconceived notions of what was important, of what someone told us was worth representing.

As we might expect, Whitman quickly realized the implications of photography for his own art. Whitman believed the camera was teaching us to see beauty where we had not before sought it out, to see significance in the overlooked detail. So he defined the emerging American poet as an embodied imagination on the lookout for whatever had before been judged to be trivial or insignificant; like the absorptive camera, “The greatest poet hardly knows pettiness or triviality,” he wrote; “If he breathes into any thing that was before thought small it dilates with the grandeur and life of the universe. He is a seer …” Over his adult years, Whitman had an increasingly high regard for photographers, for the way they made the actual things of the present suggest ideals and possibilities, for the way they made the overlooked or discarded details of the world glow with a newfound beauty, a redefined and unconventional kind of beauty that many would persist in seeing only as ugliness. But Whitman knew that ugliness and evil were often what people called those things that did not fit their preconceived categories of preference, that cluttered someone’s conception of neatness.

And all these photographs of himself taught him something about a democratic identity, too: he was of the first generation of humans who could track their own aging through a series of visual traces of the moments of their lives. When Whitman sorted through this clutter of images of himself near the end of his life, finding, as he said, “new Walt Whitmans everyday,” he began to wonder about the nature of identity: whether it was “evolutional or episodical”—a unified sweep of a single identity or a jarring series of new identities. “Taking them in their periods,” he asked, “is there a visible bridge from one to the other or is there a break?” Whitman tried to maintain the faith that his photos finally were like the catalogues in his poems, an infinite and contradictory variety that piled up a wild randomness that created a unity. We are all, every one of us, united states–single, separate individuals, many of them, a contradictory assortment of real and potential people, a democracy of possible selves. And to realize that fact is to always represent and be representative of democracy.

Like Whitman’s democratic photographic field, cluttered with an ever increasing fullness of existence, this University is getting more cluttered by the day—more programs, more ideas, more possibilities, more variety. We are working hard now to assimilate into our teaching and our research, into our very thinking, the vastly cluttered new absorptive representative tool that we call the Internet or the world Wide Web–the new ultimate democratic representative, an unending hypertext of multiplicity and contradiction. Think, for a moment, of this university community as a vast, evolving democratic poem, as we gradually learn together—through all kinds of new tools and structures and intersecting disciplines—what we have been excluding; as we gradually absorb more and discriminate less; as we build a structure as cluttered and surprising and diverse as a Whitman catalog. The opposite of di-versity sounds like it should be uni-versity, but the dynamics are changing: the university is now dedicated to becoming a decentered center, a unified multiplicity, a uni-di-versity, devoted to discovering or inventing what it is that still makes us one thing while we become more and more different things.

Maybe now is a good time to alter the metaphors we employ to understand our labor: maybe our students are not customers, after all, choosing among, buying, and consuming an increasingly bewildering array of educational products. Maybe, instead, they are our readers, the readers of this vast and contradictory and changing university of a poem, which exists primarily to keep generating more and better readers, readers who will talk back to us, readers with “supple and athletic minds” who will recognize their own diversity because we have awakened it in them with our diversity, readers whose imaginations will be unbridled because the subject of our university is them, each individually and all together. They are what we represent.