14th Annual Presidential Lecture Series

https://doi.org/10.17077/3pcv-itb4

Fade in/Fade out:

Aspirations of National Cinema

Angelo Bertocci Professor of Critical Studies

Department of Communication Studies

Program in Comparative Literature

The University of Iowa

Thank you President Coleman. I thank you, Dean Sims, and the nominating committee for honoring me by inviting me to address you all on this wonderful annual event and this brilliant afternoon. It is an honor I cherish personally, yet an honor that extends to my colleagues and students who make and study films at Iowa, for it honors the subject we have given ourselves to. All of us appreciate—every day—the privilege of working at a university which accorded cinema such stature so early on and which continues to support it. I came here from Columbia in 1968 because this was the university that took cinema most seriously. I proudly identify myself as the first doctoral student Sam Becker recruited when he became department chair that year. But I didn’t remain closed in his department, following my subject wherever it led on a campus that encouraged one to move outside of standard disciplines in search of a subject or a method. Even before the creation of the Institute for Cinema and Culture, films played in an interdisciplinary manner on this campus, allowing me for nearly 30 years to interact with so many of you. A gathering like this is what cinema seems always capable of energizing. Even if I am a bit sheepish about the rather grand ideas this occasion has encouraged me to formulate, I am confident that the still images I click off for you—plus a ten-minute clip of an amazing film I am holding for the crescendo of my talk—will stimulate conversations in the reception afterwards and beyond. With images to look forward to—prepared and projected by Sally Shafto—let me venture to lead us into the mortally serious terrain of “nation and nationalism” where cinema, from its inception, has played its variable roles.

Fade in: cinema inherits from the 19th century the model of grand novels, paintings, and histories confident in the idea of the national. Fade out: Independence Day and the re-release of Star Wars predict the end of nations, at a time when we enter a new age of entertainment media that has already altered what it means to go to the movies. The term “national cinema” highlighted in my title in fact marks just one phase in cinema’s century long relation to the cacaphonous discourse of nation, the phase, just before World War II, when this shifting relation came neatly into phase, cinema and nation inflating one another. Talk of the dissolution of nationalism after World War II is accompanied by two other phases of cinema, not so congruent with nation, the “modern” and “postmodern.” I mean here to track—and to celebrate—the changing “idea of cinema,” as philosopher Gilles Deleuze calls it, interacting with changing ideas of nation.

This talk was conceived in the nuclear afterglow of Independence Day (Figure 1L), and in the fading red flare of The English Patient (Figure 1R), two films that critics this year confidently tout to be what the movies have always quintessentially been. The first, a mega-film that the New York Times declared to be our version of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, stages a drama of survival that brings about the erasure of all the world’s borders and the creation of international union under the threat of an extraterrestrial invasion. Submitting to a directive from the President of the United States are peoples from all nations, including unidentified peoples from Northern Iraq whom we know to be involved in national conflicts but who now lay aside their local disputes to join the global cause. A super-nation is born on “Independence Day” whose single border is the stratosphere, the penetration of which triggers the spectacular climax. This is meant to be a momentous film in which “Alle menschen werden Brüder” (Figure 2). And as an after-effect, in this new world order, movies like Independence Day may travel undeterred to every part of earth. The globe is as smooth as it looks from outer space, the film declares. Images and currency should race around it unimpeded.

Ever since D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (Figures 3L and 3R), films have dreamt of the unity of humankind (and of universal distribution as well). In a sense, every film recapitulates this dream in its production process as it is delivered whole and breathing after a tortuous labor of birth. Two hours of coordinated images and sounds emerge only after noisy struggles involving different points of view, and often conflicting talents and sources of money. Films, like nations, are negotiated entities that present themselves as wholes, though sting with contradictions. The apotheosis of heavenly communion that concludes The Birth of a Nation ignores the racial division it abetted.

Into this drama between aesthetic unity and the threat of dispersal and annihilation, the “English patient” now enters—the character I mean—whose body deteriorates to extinction before our eyes as it exudes a final spew of words that become the images in flashback of a desert romance. A marvelous scene ratifies the judgement of Time magazine that here is a movie reminding us of what the movies have always been able to do. In the darkness of the Piero della Francesca chapel in Arezzo, Kip ties Hana to a rope and, with the aid of a pulley, hoists her to the ceiling where, flare in hand, she is swung from fresco to fresco, illuminating huge faces, glorious in their vintage color. Gliding across the walls, directed by Kip who controls the ropes below, she imparts movement to these pictures, bringing the past to life as she skips from long shot to extreme close-up, her face astonished, her eyes aglow, the perfect spectator at the movies (Figures 4L and 4R). This scene, an emblem of cinema, finds its echo within the English patient’s tale when he and Katherine see the pre-historic drawings on the wall of that lost cave in North Africa. Their flashlights discover the figures of animals, bringing them to life after the other, like a proto-cinematic photo series by Eadward Muybridge. Katherine will expire in the ultimate darkness of this Plato’s cave, her bonfire and then her torch giving out so that she literally has nothing left to look at or to imagine.

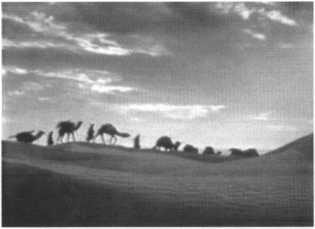

I conjure these two films today in part because it is possible to do so. The cinema still maintains so broad a reach that l can expect you to know—or at the very least know of—films such as these. And I select them as representatives of “the movies,” big-scale productions that address the two primary poles of the “movie experience” that business and art learned early on to manipulate: crudely put, the pole of action and that of passion. Independence Day and The English Patient function in the very manner Griffith began to cultivate around World War I, when “flickers” first thought of selves as features. Griffith’s action formula, coalescing in Birth of a Nation, provokes breathless expectation; whereas his passion film, Broken Blossoms, provokes reverie and what I have called “a mist of regret.” Independence Day follows the classic action plot design. The English Patient, its dark twin, inherits the complexity of cinematic modernism, where flashbacks and multiple narrators twist themselves into an exquisite braid. ugh they stake out separate zones of pleasure, both films claim to be international in theme (both are set during “world wars”) despite their provincial titles. Thus the 4th of July, after Independence Day, becomes a universal holiday, not just American; while the “English patient,” we learn, is not English at all, but a Hungarian border crosser disdainful of nationalities. His home is the unmappable Sahara, which he knows figuratively as a female body (mountains in the shape of a woman’s back) (Figures 5L and 5R). Seen from the air, the shadows of dunes are pores on her skin. To embrace the world as if it were a woman is what the ads promise, so that Miramax, its distributor, less sentimentally, may embrace the global market.

*******

Fredric Jameson coined the term “the Geopolitical Aesthetic” to compare different forms of “cognitive mapping” that the novels and films of various peoples since 1975 let us understand. “Cognitive mapping” suggests that individuals live out, depending on their culture, different styles of experience, as they pre-consciously negotiate the spaces of an increasingly opaque social environment. I want to drive his intuition back across the full history of cinema and ask you, for the duration of this talk, to accept my three periods—Classic, Modern, and Postmodern—divided by the drum-roll of a great war. These labels attract a cluster of associated elements from different zones of cinema, as the entire field of “the cinematic” bends under the pressure of socioeconomic and cultural change.

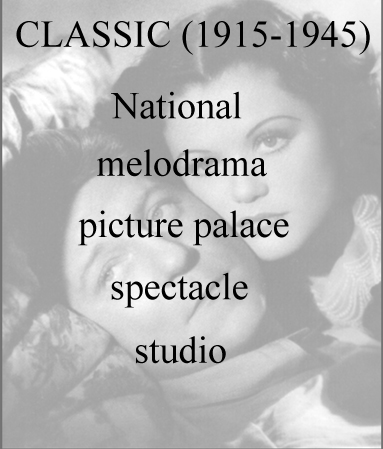

| Classic (1915–1945) | Modern (1945–1975) | Postmodern (1975–) |

|---|---|---|

| National | Federal | Nomadic |

| melodrama | neorealism | pastiche |

| picture palace | art house/TV | film festival/VCR |

| spectacle | ”ecriture” | orality |

As I sketch the characteristics that distinguish each period, bear in mind that all three strains of film can co-exist (Independence Day belonging to the classic category though made in 1996; The English Patient, a hybrid, employs aspects of classic melodrama, yet is modernist in structure); I mean to point a beam of light at successive eras each of which harbors an emergent “idea of cinema”: what—and how—the cinema permits humans to think. Let us listen to this idea in dialogue with concurrent ideas of nation.

Cinema was born one hundred years ago in the full flush of nationalism, growing up most vigorously in countries confident in their flags. Almost immediately one spoke of French or British or American films. By 1912 Italy had joined this group, cinema becoming its national “body in the mirror.” Italy may well be a paradigmatic case, for cinema was explicitly recruited there in a project of nation-building where it joined an earlier effort in opera to unite the regions of the peninsula and the regionalisms of language, class, and culture under a common flag. Movie theaters from Sicily to Turin simultaneously projected the image of Maciste, the beloved hero of Cabiria, who was likewise applauded by Italian immigrants in New York and Sao Paulo, helping to constitute an “imagined community” and preparing this uncoordinated body of a nation for a head—one Mussolini would assume.

This recognition that cinema might project the nation is behind the expansive rhetoric spouted in the 1920s by champions of the new art such as Abel Gance. Gance subscribed to Griffith’s grand mission of a cinema that had assumed for our century the function of the novel and the romantic symphony in melding disparate elements and audiences. Gance likened himself to Beethoven, whose biography he filmed in 1936. While universalism seemed ascendant after the Great War (and cinema was touted as the esperanto that the League of Nations was looking for), it was Griffith who made his name with Birth of a Nation and Gance who will always be associated with the 1927 Napoléon (Figure 7). These men were national filmmakers of nations that won a world war; their international pretensions paralleled those of the nations they came from and spoke for. This was the moment of nationalism and concurrently of highest ambitions in cinema: picture palaces enthralled thousands of spectators at a time, while huge studios shaped films to the needs of this nationalist environment, shaping citizens in process.

The apogee of nationalist ideology and of this classic phase of cinema must be the end of the 1930s and the beginnings of the Second World War; let us overlay on the political map dominated by Franco, Stalin, Hirohito, Mussolini, Hitler, and FDR first the topics and then the look of the most ambitious films of that time. Gance remade Napoléon in a sound version, in 1936 the Catholic Church in France sponsored the feverishly patriotic L’Appel du silence; in Italy we have Carmine Gallone’s state-funded Scipio Africanus; in the Soviet Union Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky; in Spain Raza, an epic scripted by Franco himself; in Japan Mizoguchi’s Loyal 47 Ronin; and hovering above all these examples, Leni Riefenstahl’s unequivocal Triumph of the Will. Each of these prestige films reworks the script of Birth of Nation, wherein fragmented individuals (not yet a people) are put to the in a drama that concludes in an apotheosis of unification where citizens lifted, actually sublimated, into a mystical national body. Such scripts seduce not only the naked political rhetoric available in newspapers and speeches on the radio, but also the very condition of film spectating itself: he price of a ticket the sad and the alienated were welcomed into a palace, a cathedral of images where, gazing on a spectacle worth sands—even millions—of dollars, they could become one with their neighbors who likewise looked on dumbfounded at a coordinated image, an image of health and power and virtue, a whole image and an image of wholeness, luxuriously adorned, a “mass ornament” Siegfried Kracauer called it.

It should hardly surprise us that governments routinely commissioning heroic sculptures to stand in front of state buildings should command or encourage cinematic monuments to nationalism. The sheer scale of the image—its size on the screen—and its ubiquitous distribution made of it a rhetorical apparatus equal to the conception and to the task of nationalism. Cinema provided codes whereby spectators could recognize themselves and recognize “others”; it provided rules to decipher a confusing world, and a narrative mission sufficient to a need for security and identity. In brief, the subjects of cinema were the subjects of nation.

I have been speaking about spectators caught up in historical epics designed by ideologues. But what about popular entertainment? Did the ordinary cinema entertain national aspirations? For my purposes here, let me distill ordinary cinema into a single mode, melodrama, the cinema of passion, at the other extreme from those historical epics just discussed which were invariably “action” pictures. Of course there were many popular genres, comedy the most ample; but in the way that the movies adopted, inflated, and exploited popular love romances, melodrama embodied the cinema in toto. Clark Gable, Greta Garbo, Charles Boyer, Simone Simon, and Jean Gabin suffered and caused suffering, and they did so in one place only, on the big screen. The sighs in the audience occasioned by their plights express a cinematic aspiration in league with nationalism. The hypnotic identification that melodrama induces has been said to be the medium’s chief distinguishing trait, a medium that Christian Metz would call, in a most famous book, The Imaginary Signifier.

One man who glimpsed the relation between the culture of romantic love, the hypnotic experience of cinematic melodrama, and the ideology of nationalism was Denis de Rougement, known today, if at all, as the author of Love in the Western World. Writing in the 1930s, De Rougemont thought the cinema provoked passion, which in his words was an “allergic reaction” where the organism produces an overabundance of feeling in response to a minor disturbance. Cinema functions in just this way: a furtive kiss drives the hero to glorious self-destructive acts. Passion is an approved addiction for on-screen heroes, and for off-screen spectators entranced by the imaginary signifier.

De Rougemont’s concerns became more than academic in June 1936 when, observing a Hitler rally, he unexpectedly experienced a primal urge to abandon himself along with thousands of others in the spectacle of a gigantic totality. Fascism asks just this of individuals, the nation being all sacred. But de Rougemont countered such collective surrender with “personalism,” a political philosophy wherein the individual wills itself into social existence as person by participating in networks of family and community. He took fascism and soviet communism to be pathologies that produce dependency, the community having outgrown the personal. De Rougement insisted that social and economic concerns be adjusted to the scale of the person, not vice versa. Scale is the key. It is one’s neighborhood and the land one traverses routinely that one belongs to. Personalism explicitly countered nationalism’s hunger for centralization and homogeneity with a modern alternative: “Federalism,” the negotiated amalgam of localities of difference.

Was it at the University of Frankfurt, where he taught French literature in 1936, that de Rougemont conceived Love in the Western World, his sweeping anthropology of European civilization? Conjugating, then critiquing, passionate love and national fervor, this book stands as his personal and personalist rejection of the alluring voice of Hitler and the more alluring strains of Wagner, both of whom he heard and felt that year. Delving into “the Tristan complex” he equated Hitler’s appeal with the “exquisite anguish” infinite longing that Wagner produces. De Rougemont quotes Hegel in his conclusion, “the Faustian search for the sublime intensity of experience … ultimately realizes itself in death, in the final privation when one feels more alive than ever and living dangerously and magnificently.” This obsession with a dangerous and magnificent eroticism is pervasive in the West, de Rougemont argued, its consequences visible in an escalating divorce rate, in l’amour fou of Surrealism, and, he daringly added, in the battlefields of wars that themselves have surpassed all limits, total wars, World Wars. In all these cases, passion feeds on escalating obstructions, producing a friction of suffering that authenticates the experience, but that must ultimately mount to suffering of death where lovers annihilate themselves in the quest of transfiguration. De Rougemont is explicit: “For a people to believe in their spiritual union, they must suffer danger, including the danger of an annihilation which, whether as passionate lovers or as national subjects, they wholeheartedly accept” (de Rougemont, 44–46).

His book traces this complex to the new literature of impossible love created he troubadours of the late Middle Ages in league with dark orphic heresies. From them grew the main trunk of western literature: Petrarch, Romeo and Juliet, The Sorrows of Werther, and Wagner. This poetics of “Sehnsucht” was adopted wholesale by filmmakers to motivate their pictures of adultery. De Rougemont found this longing exploited by the Third Reich which sang a hymn of the transmutation of self in a higher unity, even in immolation. Raised on this poetics of desire a whole civilization could be pulled into de theaters and toward massive political rallies where they expected to emerge transfigured.

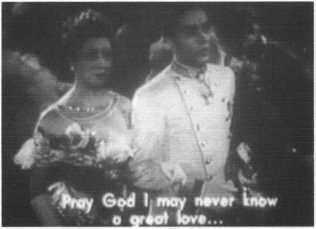

De Rougemont hadn’t far to look to discern degraded avatars of Tristan projected at the movies. One of France’s most popular films of 1936, and one he surely saw—it being a perfect example of the mapping of nationalism onto melodrama—was Anatole Litvak’s Mayerling. Charles Boyer and Danielle Darrieux star as the doomed lovers in this account of the abject ides of crown prince Rudolf of Austria and Maria Vetsera in 1888. Forced a political marriage devoid of feeling, Rudolf whispers to his mother in the wedding procession near the opening of the film, “Pray God I may never know a great love” (Figures 8L and 8R). But on the fairgrounds of the Prater he discovers such a love, only to find it thwarted. The climax that brings the lovers into completely private intimacy occurs in the most public and hostile of spaces, a State ball, where the pair is gaped at by the scandalized guests. Rudolf asks Maria if she would follow him on the furthest of journeys; she comprehends his meaning, as does the camera which dissolves from a two—shot of the couple to an extreme close-up of her serene face as she answers: “avec toi, oui.” Before we dissolve back to public time, Maria has visibly let go of her soul, joining it to the prince’s in their destiny.

Nearly plotless, Mayerling moves forward on the inevitably increasing anguish of its lovers, whose passion mounts with each separation. After the ball, Rudolf gathers his beloved in his arms and leaves for Mayerling, the isolated hunting estate already hushed by an early snowfall. Accompanied by a Liebestod musical motif, the couple retires for their final night. Then the trusting Maria falls asleep, secure that her prince will take them into oblivious union. “A grief-bowed Romeo,” wrote the New York Times, “before the still form of his Viennese Juliet … They are the only people in their world; the rest are shadows; and when the shadows grow too black, they leave it.” A gunshot follows, with a tasteful cutaway. And then the second shot as their fingers intertwine. The critic claimed to have been dragged into this world, “carried breathlessly,” he says, “along an emotional millrace, exalted and made abject as the dramatist directed.” Such is the lure, and such the pleasures, of engulfment in the classical paradigm.

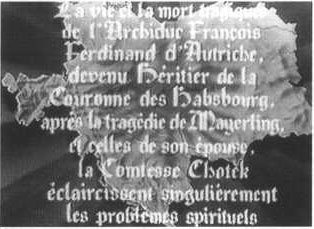

In the U.S. Mayerling was hailed “the best film yet turned out in France” and it was followed by other grand tragedies of love and death, by Katia and Quai des brumes, and La Bête humaine (Figure 6) (the top grossing films of 1938; figure beneath “Classical” table above) and by Max Ophuls’s Le Roman de Werther (Figure 9) which de Rougemont surely saw on the Champs Elysées where it premiered the spring of that year when he was writing on Goethe. The title of Ophuls’s next film Mayerling to Sarajevo, and its opening title shot, link the love suicide of 1888 to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of the Great War (Figure 10L and 10R). Production of this film was delayed by the onset of the second total war, which it cites in a prescient epilogue. Then during the German Occupation there crested another Tristan wave, including a novelization of the myth and Jean Cocteau’s apotheosis of the Tristan phenomenon, The Eternal Return, the single most popular French film of the Occupation period.

Had de Rougemont looked for cinematic alternatives to this dominant romantic trend, had he sought an emerging modern cinema that shared his federalist view in politics and his personalism in ethics, he might have pointed to Jean Renoir’s The Crime of Monsieur Lange which played concurrently with Mayerling in the winter of 1936 (figure 11). Renoir’s fable of workers who transform the publishing company that employs them into a “cooperative” hinges on a love story where—refreshingly—passion is replaced by elective affinities, that is, by friendship, humor, and respect. No “grand illusion” hovers over this couple. Their allegiance is to their courtyard and to the collective life they establish there.

In 1937 came Renoir’s most famous film, explicitly called Grand Illusion, and dedicated to undermining the borders and military fronts by which nationalism tries and fails to segregate the shared interests of ordinary people. The cooperative societies that the prisoners of war spontaneously establish and, when dispersed to other prisons, establish all over again, express Renoir’s belief about self-governance and about the federated coexistence of neighboring groups, even groups that have been told they are at war. In place of a passion that consumes a couple in an ecstatic or fatal union, Grand Illusion treats the love of the Frenchman Maréchal and the German woman Elsa as a process of accommodation to difference: difference of nationality, language, occupation, even marital state. Dependent on the Jew Rosenthal as interpreter, they come to the fullness of love aware that their separate lives have been brought together in affection for a time. With Rosenthal and Elsa’s young daughter they form a makeshift rural family. This is the family unit Renoir espouses, one based on respect, limited demands, and on an unlimited concern for the welfare of others. In the final shot, Maréchal and Rosenthal, forced to leave, strike out across the invisible border toward Switzerland, haven of small human groups amidst the inhuman drama of opposing nationalisms. Did I mention that Denis de Rougemont was Swiss?

*******

With Renoir, we have already left behind the classic age end made early entry to the modern mode. In 1938, his contribution to the spate of national historical epics, La Marseillaise, provided a different model of “union,” essentially a comic model featuring commonplace events and common people. Ignoring the deeds of the heroes of history books like Danton and obespierre, La Marseillaise carries the tone of the Jacobin meetings it represents where many have their say and where a song uniting them all seems bound to emerge, sung in various registers but sung together. On the Paris screens while Love in the Western World was being penned, La Marseillaise disappointed even leftist critics who cried out for an heroic view of history and of nation, not the multi-perspectival federalism Renoir insisted was the mandate of the Popular Front.

Renoir responded to this criticism with a bitter version of the Tristan tale, The Rubs of the Game (Figure 12). This foundational film of the modern era opens when the dashing aviator, André Jurieu, having crossed the Atlantic and descended from the clouds, proclaims across the radio waves his forlorn love for the aristocratic Christine. Courtly and upright, Jurieu barges straight into the Marquis’ estate intent on taking his wife. But Jurieu is out of place; more accurately he is out of his time, for the time of romance is over, and Renoir’s film, coming out during the “phony war” of autumn 1939, unrolls as farce. And it is a cruel farce, Jurieu being shot down like a rabbit. If The Rules of the Game points directly to the war, it points as well beyond to a critical, uninflated modern cinema and to a post-nationalist Europe that would temporarily abandon the myth of self-abandonment, whether in tragic love some almighty leader.

When we track the emergent “idea of cinema” in the modern era, we move from Renoir to Roberto Rossellini and his 1946 Paisa, and from this neorealism to the French New Wave of Truffaut and Godard who knew both Renoir and Rossellini. It was the film Paisa that gave rise to the idea of the film essay, of cinema as a form of writing, écriture. The camera, it was said, had become a pen, wielded by a “director on a set, alone as before a blank page,” an auteur.

For the next thirty years the auteurs of modernist cinema would often use impoverished technical resources to get at something that grand national and studio melodramas seldom touch, the existential politics of ordinary humans (frequently, as in Paisa, non-actors), presented sometimes with the starkhess of neorealism, at other times (as in Hiroshima, mon amour or La Dolce Vita) through the most ingenious narrative schemes and elaborate subjective camerawork. Paisa spawned new waves everywhere, in France, in Poland, in Latin America and Japan, all essentially anti-state national movements. I say anti-state, for the new idea of cinema resulted in an interational art cinema and in federations of film societies at odds with state-regulated television and with an old political idea now going under the name, “cold war.” In this environment, the art cinema after neorealism was uniformly alienated from or critical of lofty national images, playing the role of personal, authentic discourse, like that of novels and essays.

While this shift from the classical to the modernist mode can be tracked in the fiIms themselves (Renoir to Rossellini to Godard and beyond), it is equally visible, as my table suggests, in the altered conditions of a changing film culture where the new “idea of cinema” emerged. After the war serious critics spent less time in gargantuan picture palaces and far more in the proliferating but intimate art houses. Take one example: in 1945 Robert Bresson’s Los Dames du Bois de Boulogne, a refined adaptation of a Diderot noveIla, opened in Paris at the ornate Rex Theater with a seating capacity of 3500, where it failed ignominiously. Four years later it was revived at the “Festival des films maudits” organized by Jean Cocteau and André Bazin. In 1954 it played a long run at a small Parisian art theater where Truffaut, Godard, and Jacques Demy saw it repeatedly; inspired, they would quote the film in their own New Wave works which likewise were distributed primarily in art houses. Indeed, the idea of cinematic citation thrives in art houses where sophisticated audiences might be expected to respond to the subtleties of an auteur’s écriture rather than crave a repetition of some studio spectacle. Such a self-conception permitted cinema to be cautiously welcomed into university life and eventually into a curriculum, where, more than anywhere else, this mode of cinema remains. This is the cinema that brought me and many others here, the complex modernist cinema, a cinema seemingly equal to our times.

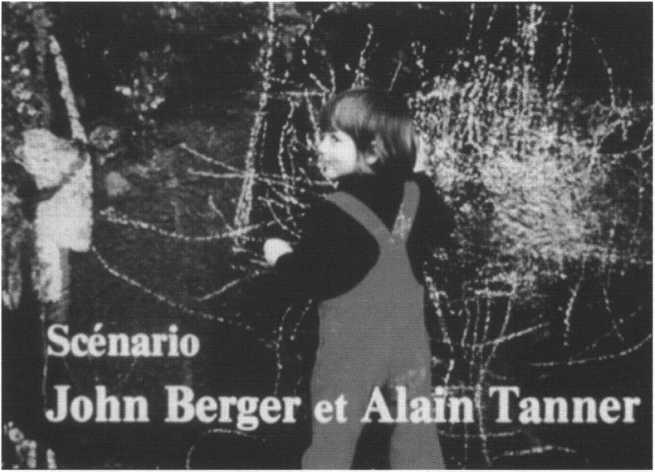

But just as cinema gained a foothold in the academy, it was already mutating into something else, which few of us at the time could have fathomed. In 1968 nearly 10 percent of all US theaters were art houses, yet in the next decade these began to close as the youth and energy of all the new waves no longer echoed in the public sphere, even before the advent of the VCR. 1975 is the year of a film that sums up and closes off the modernist era, one I bring up on every occasion possible: Jonah Who Will be 25 in the Year 2000 (Figure 13). I bring it up today because it is Swiss, because it explicitly cites Renoir’s popular front films, and because it employs the critical expressivity of the New Wave. Jonah stands directly in the modernist line; but in its nostalgic tone, and wildly prophetic title, it knows this to be the end of the line. Plotted out like an amalgam of cantons, Jonah follows eight quite different characters who, in the aftermath of 1968, haphazardly gravitate to a farmhouse outside Geneva where they take up a cooperative arrangement, including growing organic food and educating their children. In its style and structure Jonah strives for that “equilibrium” that Renoir magically achieved 1930s, a democratic aesthetic where multiple characters and incidents play across a dramatic field that could never be represented in a single “plot line.” Emulating this approach, the director Alain Tanner seems to relinquish the power of “directing” all the technology and all the actors at his command in favor of balancing the multiple goals, events, styles, and personalities who contribute to the loose community that takes shape under the benevolent of a mobile camera. Opposed to the imperious directorial command of, say, a Max Ophuls or in our day a Steven Spielberg, this federalist style suits “minor” cinemas in their self-defense against international entertainment conglomerates that wrap themselves ever more tightly around the globe. It is minor in being (like de Rougemont) Swiss rather than French, in taking its distance from Geneva and Hollywood, and in finding its way to a diminished federation of art theaters. It points, albeit with some dread, to a new world order and a new function for cinema.

*******

And what about Jonah, that young angel of cinema, now that the year 2000 is upon us … Jonah, who was born just as Vietnam ended and just before Star Wars opened the age of Global Hollywood? He has access to fewer images, that’s for certain. Of the 2500 feature films I estimate are made each year, the 400 made under Hollywood’s aegis absorb well over 90 percent of the world’s screentime. At the last film festival I attended, in September in Montreal, 234 features were on display, including three from Israel, two from Romania, one each from Kaxutstan and Kirghizio. France was involved in 60 films. Pitifully few of these 200 foreign films will manage to break into the ever-diminishing New York market that once sported twelve art houses. For the most part, these films will simply circulate to other festivals. Thus the “idea of cinema” has migrated from the imposing studios of the classic era in Hollywood, past the elite auteurs of modernism centered in Europe, and now into the very principle of migration itself, whose centers are the nowhere locations of outlying lands, like Ireland and West Africa (Figure 15L), both bubbling with images today although neither participated in the classic or modernist phases.

William Butler Yeats could have had cinema in mind when he distinguished Ireland as a nation where tradition flashes up in transient images, given off through the anecdotes of essentially oral poets, a nation of clever songs rather than of the thick novels and history books that anchor mighty England. England was to him what Hollywood is to me, the smothering status quo, heavy and predictable. Ireland, Yeats believed, practiced a “nomadic” mode discourse, linked to the traveling people of its countryside who recast their identity each night around the fire. This fire has become the projection light of one of the most exciting cinemas on the globe today, resisting, as it so often does, the homogeneity of the Anglo-TV and American movie culture. Imagine Ireland, the size and population of Indiana, where 25 films are currently in production, many of them literally off-beat, nomadic representations of people whose identity is in flux.

The rough binarism I am drawing between “minor” cinemas and Hollywood plays out in the realm of media the struggle that Gilles Deleuze elaborates in his provocative discussions on nomadism. Urban centers and their institutions aim to project themselves in striated coordinates as far as they are able. City streets and thoroughfares cut up the variances of land forms into rectilinear units, just as the variety of values which that land produces are homogenized by the market economy. The nomadic alternative responds to this threat in a literally grass roots way by coming up with provisional practices suitable to every landscape (geographical and political).

The nomadic, metaphorical site of my postmodern category shares with federalism a belief in the importance of self-determination through the versatility, scale, and coordination of participating units. But it exceeds federalism in emphasizing the protean character of such units. De Rougemont’s vision of a federation of cantons still presupposes the allegiance of people to the land they are born and live on. By definition the nomadic flows across boundaries. Nomadism names a style of resistance for the postmodern age, the age of global, rather than state, capitalism.

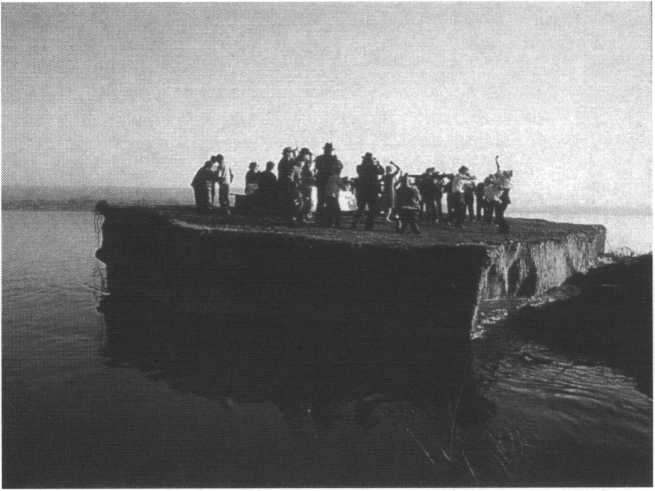

Let Hollywood colonize the globe and let nations erect the pretense of autonomy in their state television industries. The idea of cinema survives and now emerges in movies assembled in scattered locations, then bicycled to outlying viewing sites and the nomadic culture that awaits them (Figure 15R). The symbol of its itinerant location is the film festival. The movies that today think the national beyond the nation travel from Rotterdam to Toronto to Berlin. Critics literally follow this moving camp to catch the rumor of cinema.

For today cinema and, let me add, nation are ideas passed down and passed around as if by word of mouth, transitional ideas that exist mainly in transit, in passage. Hence the aptness of “nomadism” and of orality as metaphors for a resistant cinema, one “beyond the pale” of the global, as they would say in Ireland. Next week I will try to catch that rumor, making the long flight to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso for the biennial FESPACO, the Festival Panafricain du Cinema, celebrating an unauthorized cinema that commands no screens, has theoretically no space to exist, an oral cinema whose rumble I will bring back to my students. Orality is ceaseless in Africa; it reasserts and maintains the social fabric in lengthy greetings, literally crisscrossing the community to make certain that all members are available, like a computer periodically testing its memory. Orality represents and creates the social cohesiveness of those African societies that some (following Yeats’s view of the Irish) would have been tempted to think of as organic in the literal sense.

In this environment, the cinema cannot choose but be linked to the griot, the African storyteller, whose most powerful function is as a medium through whom tales and wisdom are passed down. As with the trance dancer selected to be inhabited by an ancestor come back to interact with the group, the past erupts publicly in the griot usually at night around a fire, joining the group in a communion rite. Determined to adopt this function, the filmmaker Soulymane Cissé produced a masterpiece in 1987, Yeelen. He provides an unforgettable example of the griot’s power in an anecdote associated with this film. The night before shooting was to begin in the Bandiagara cliffs of the Dogon people of Mali, the old man he had chosen to play the role of the soma charmed the cast and the crew around the fire with an incantation, a sinuous linguistic evocation that eventually conjured a benevolent Boa spirit out of his cave in the cliffs.

Far from civilization, seated around a fire … we listen with more interest than we ever have. We don’t know if he is spooking the truth or imagining things, but we listen with passion. They say his words reach beyond the memory of men. The great Boa, did he really come? Does that snake truly exist? For us Malinke people, our imagination had had a rendez-vous. Even if the Boa dididn’t pass through our camp, it is true that at a certain moment, something had hovered those cliffs of Sangha the night before shooting Yeelen.

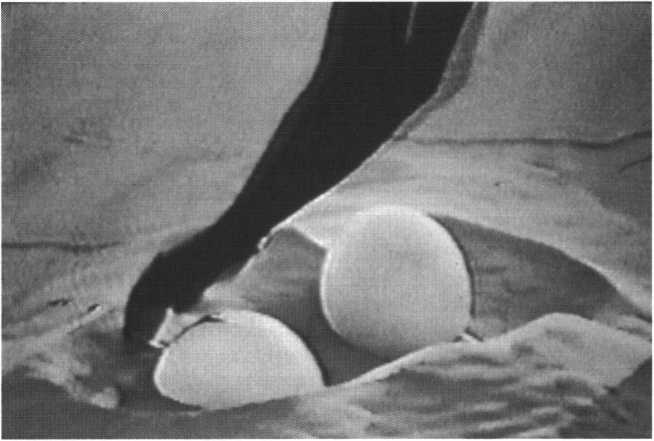

Many intellectuals like Cissé have wanted to preserve the possibility of such a communal past, alarmed by the transformation of memory through technology, including the technology of writing. He is among those African filmmakers for whom the cinema amplifies, rather than contaminates, oral culture. Like the child who digs the huge eggs from the sand in Yeelen’s scene (Figure 16), this film together with its director and its spectators stands expectant before a future full of such a past. Let us listen to the griot.

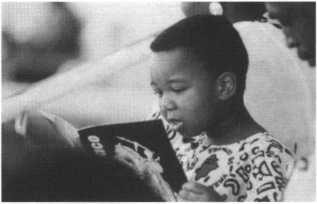

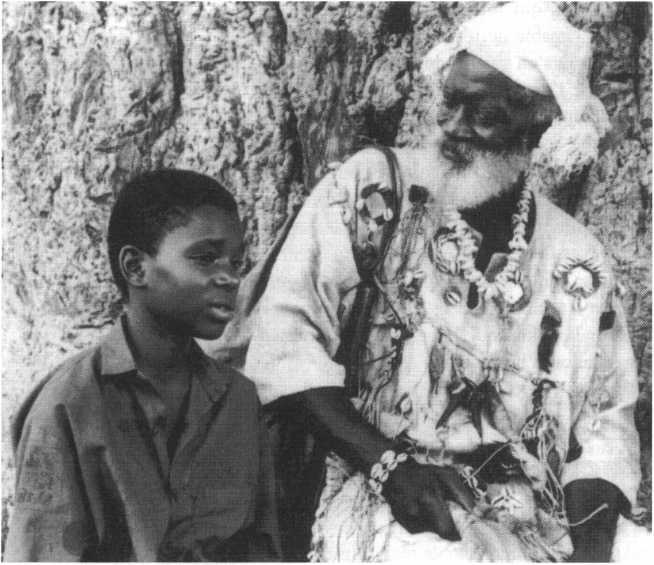

I’ve brought a griot here today in my ten-minute version of one of the revelations of the last FESPACO: Keita, also called From Mouth to Ear (Figure 17). This fable features an ageless griot out of whom the story of the birth of the worId and of culture emerges as he wakes to bring this story to a young boy, another Jonah on whom the future depends. The griot’s pre-nationalist values run into conflict soon enough with the educational bureaucracy of the State. Let’s watch the first seven minutes and then the conclusion; you’ll understand the plot and be charmed by the style.

The clever structure of this film, like mirrors facing each other, has the hunter awaken the griot who in turn recounts the tale of this very hunter who centuries ago predicted for the king of the Mande the actions that would in fact make him legendary. Paradoxically, the hunter gives life to the griot who gives life to the hunter who initiates the tale of Sondjata that the griot now relates to the boy. And the boy must continue the tale. Alone by the great baobab tree he must continue the search himself.

And continue it he did; for in fact the actor playing Djeliba is among the most famous griots of West Africa, Soujite Kouyate, and his son—”in real as we say—Dani Kouyate, who heard these tales from his birth, grew up to direct his father in this very film. Dani’s search took him to Paris and to a doctorate in ethnography and a degree from film school. He came back to become himself a modern griot and to pass on his father’s tale on film, instituting the culture of his nation.

But what nation is that? Hybrid and allegorical, Keita asserts an alternative to national history, education, and cinema. When interviewed at the festival, the question of Kouyate’s own nationality arose. His film represented Burkina Faso, yet Dani Kouyate claims to belong equally to Mali. In fact he prefers to be called Malinke, a nation of people inhabiting several countries, negotiating borders, customs, taxes in the cleverest, most nomadic ways.

Thee incongruity posed by the concept of nation at a festival with the word “Panafrican” in its title reached its height after the crowning of Guimba from director Chiek Oumar Sissoko of Mali. In the town of Konna in central Mali that I visited the day after the festival, a full-fledged celebration of national pride broke out with news that Guimba had won. Fireworks were lit; the town’s generator was wheeled out so that a string of electric lights could make this night special. I celebrated too, and I asked the locals if they had seen other films by Sissoko, or any by Souleymane Cissé. But they hadn’t. Nor would they see Guimba. They couldn’t imagine what it might look like. Their weekly movie comes by way of an itinerant projectionist who peddles only Hindu melodramas and kung-fu action films. African films exist only as rumors in Africa. But you can see one or two in the USA. In fact you don’t have to run very far to see Guimba; you just missed it; it was at the Bijou last week.

How potent can such a nomadic cinema be? How strong is this “idea of cinema” when stacked up against the global Hollywood system? Djeliba in Keita has already told us: “Do you ever wonder why, in the stories, the hunter always kills the lion? Its because the hunter is the teller. If the lions could tell stories, they would win from time to time.” Keita is a tale told by a lion, a lion roaming the sahel. Not far away are those unmappable sand dunes of The English Patient. But whereas the narrator of that global film expires in the telling, Dani Kouyate and his father are both quite alive. Doubtless I will see them next week in Ouagadougou where scores of new films will flicker from morning to night in a brief illumination, more remarkable by far than the international nuclear blast of Independence Day.

I close with a final image, in fact the final image of the film that won the Cannes film festival in 1995, but, because no international distributor has had the courage to pick it up, has yet to have a theatrical screening in this country: Emir Kusterica’s Underground (Figure 18), a film that bears a second title, perfect for my conclusion: Once there was a Country. The numerous protagonists and even more numerous antagonists of this four-hour circus of a film about Yugoslovia since World War II, find themselves at a picnic by the side of the sea in a finale reminiscent of that of Fellini’s 8 ½.. While gypsy music plays, the characters cavort in character, seducing and crossing each other, all the while consuming food and brandy. Suddenly an earthquake cracks the land, sending them floating off to sea. From an aerial view, we watch them continue to argue and berate each other, now locked permanently on an island whose shape of course is that of Yugoslavia.

Blistered by French philosophers as well as by East European politicians for presenting a Serb, not a Yugoslav view (whatever that would be), Kusterica, one of the great filmmakers of our day—my favorite in fact—angrily announced his retirement from film. “Once there was a country,” he as much as said, “and once there was cinema.” But neither is the same today. Both are fading out.

I’ve just learned, however, that Kusterica, maker of Time of the Gypsies, is traveling from France to Bosnia and back, trumping up another fugitive project, fugitive and minor like the people (I’ll not say nation) he knows so I how to frame. That’s the rumor, at least; the rumor of cinema. I’ll be listening closely.

Special thanks to Janice Frey for creating my overview slides of the Classic, Modern, and Postmodern phases.