4th Annual Presidential Lecture Series

https://doi.org/10.17077/16xt-yli0

“History Will Do It No Justice”:

Women’s Lives in Revolutionary America

May Brodbeck Professor in the Liberal Arts

Professor of History

The University of Iowa

Introduction

This is a day on which we celebrate scholarship. I am particularly happy that the scholarship we celebrate is women’s history, a field which, when 1 was in graduate school, was so neglected that we were unaware that it once had flourished. The modern feminist movement, like its predecessors, has been accompanied by a hunger for women’s history. The first women’s movement of the mid-nineteenth century had been accompanied by the historical investigations of Lydia Maria Child and Elizabeth Ellet, as well as careful documentation of its own experience by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The suffrage movement of the Progressive era had been followed by the first wave of graduate trained feminist historians, among them Mary Beard, Caroline Ware, and Mary Summer Benson, who went to college and graduate school in the teens and 1920s and published their first books in the 1920s and early 1930s.

I feel lucky to have done my work in the Department of History at Iowa. In the early 1970s, to teach women’s history was a political act. In other universities, historians who wanted to teach women’s history often had first to engage in bitter fights with department chairs, deans, and curriculum committees. Here at Iowa, Sydney James, who then chaired the history department, asked only one question: “Do you want to teach on Tuesdays and Thursdays or Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays?”

Women’s history also had a warm welcome in American studies, the field of my undergraduate major, and at the time very much an outsider in the academic community.

It is also a pleasure to feel that this day is another marker in the maturing of the women’s studies program here. Now more than 12 years old, and one of the oldest in the country, we enter our adolescence as a group of warm colleagues, under splendid leadership of Margery Wolf, energized by national trends that support some of the most exciting interdisciplinary scholarship of our generation.

Speech

My title comes from a rueful observation of Elizabeth Ellet, the first historian to address extensively the relationship of women to the American Revolution. Ellet was a writer for popular periodicals; her grandfather had fought in the Revolution. In 1848 she published two volumes of biographical sketches of some 60 women who lived through the American Revolution. In her preface, Ellet addressed the practical problem of recovering their lives.

In offering this work to the public, it is due to the reader no less than the writer, to say something of the extreme difficulty which has been found in obtaining materials sufficiently reliable for a record designed to be strictly authentic .... Inasmuch as political history says but little—and that vaguely and incidentally—of the Women who bore their part in the Revolution, the materials for a work treating of them and their actions and sufferings, must be derived in great part from private sources. The apparent dearth of information was at first almost disheartening . . . Of the little that was written, too, how small a portion remains in this . . . manuscript-destroying generation!

Ellet interviewed and corresponded with elderly survivors and with the children and relatives of her subjects. After a while, her problem ceased to be a problem of finding information and became the analytical problem of how to arrange and interpret it. She did not solve the analytical problem, but she did begin to sneak up on the solution.

Ellet deduced that there had been at least two sets of equally authentic wartime experiences, documented in different ways. Attested to by public records, “the actions of men stand out in prominent relief,” she wrote. But the actions and influence of women occurred in the private “women’s sphere,” and for these activities documentation was deficient. Thus there were two perspectives on the Revolution, as there were of any great event, waiting to be written about; and of the two retrieving the women’s perspective was the more challenging and the more difficult. Retrieval was difficult for the technical reasons of the paucity of official and personal records, for the inattention with which women’s behavior was regarded, and for the scorn with which records of that behavior were treated by a “manuscript-destroying” generation. But it was especially difficult, Ellet suspected, because women’s history necessarily had a distinctive psychological component. She thought that women shaped the history of their generation by personal influence, by the force of “sentiment,” by feeling. This second factor, inchoate, ill-defined, which represented the difference women made, could not be measured and was not easily described. “History can do it no justice.”

Ellet wrote in the now dated language of nineteenth-century romanticism, and it is easy to read her work in a way that stresses its naive celebration of domesticity and service, its simplistic narrative strategies, and its implicit racism. (She thought it was generous when a slave who had saved his master’s plantation was rewarded by easier work and, only many years later, by the purchase of his wife from a neighboring plantation so they could end their lives together.) I would not agree with Ellet that sentiment and feeling are a female monopoly. But I do believe that it was an analytical improvement to recognize that there were at least two wars, a men’s war and a women’s war (just as there was a soldier’s war and a civilian’s war); that the two merged and often interacted; that one might serve the other but was not necessarily subsumed by it. As Justice William O. Douglas observed many years later, “The two sexes are not fungible.”

Ellet began by recovering the stories, mostly of patriot women but some of loyalists, and getting them into the record before time ran out. She told the stories of prominent women like Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and Martha Washington, but there were also the women of Groton, Massachusetts, who, after their minutemen husbands had left for Lexington and Concord with Colonel Job Prescott, guarded the bridge on the road at the town border “clothed in their absent husbands’ apparel, and armed with muskets, pitchforks, and such other weapons as they could find,” arrested, unhorsed, and searched a Tory messenger carrying dispatches.

Then Ellet went further. She had written a distinctive women’s history and discovered in the process a large audience for her work (two years after its publication Women of the American Revolution was in its fourth edition). In 1850 she tried to write a different book, a book that placed gender at the narrative center of the revolutionary experience, a book that would tell the history of the American Revolution from the perspective of both men and women. That book bears a wimpy title: Domestic History of the American Revolution, but it turns out to be a surprising book. Ellet really does do a measure of justice to the women whose life experiences she had uncovered for the 1848 series of biographical sketches. Domestic History is the only history of the Revolution—perhaps of any war—I have read that actually spends as many words on women as on men. The book is not distinctly a “women’s history”; it seeks to be holistic. It offers a narrative of the war years, arranged by standard political set pieces: the great battles—of Long Island, of Saratoga, of King’s Mountain, and so forth, all the way to Yorktown; the winter at Valley Forge, the treason of General Arnold, the mutiny of the Pennsylvania troops. But Ellet’s text treats these episodes briskly, and in that way makes room for women’s boycotts of British goods, women who contributed massive quantities of food to armies on the march, women who collected substantial contributions of money and supplies. As the war proceeds, clashes of armies alternate with accounts of women’s activity and response.

Sometimes the women are victims: the confrontation at Lexington and Concord is followed by a woman’s memoir of her flight from Cambridge, “the road filled with frightened women and children, some in carts with their tattered furniture, others on foot fleeing into the woods.”

Sometimes women’s presence is ceremonial: “On the third day after the battle [in which the British were repulsed from Sullivan Island in the Charleston Harbor] . . . the wife of Colonel Barnard Elliott presented to the second regiment, commanded by Colonel Moultrie a pair of richly embroidered colors, wrought by herself. They were planted, three years afterwards, on the British lines at Savannah, by Sergeant Jasper, who in planting them received his death wound.”

Always it is women who maintain elementary decency when it falls apart around them. They talk back to uppity Tories, they stand up for their property rights. And a steady stream of women bring food and blankets to prisoners; among these women is the mother of Andrew Jackson, who dies of a fever caught on one of these expeditions. In Ellet’s hands, the actions of individual women often shape the occasion or the outcome of a particular battle. Mrs. Robert Murray detains Governor Tryon at her tea table long enough to give the Americans under Putnam time to retreat. And always women ride through the woods—at night, in dead of winter—to bring word to American detachments of British plans.

This riding through the woods is worth attention. Ellet’s accounts are as much a literary vision as historical reporting. They are a folk history, gleaned from the stories she heard. If we add anecdotes from the two volume History of Women to the ones in Domestic History we are left with American forests as peopled as those of the Brothers Grimm, in which instead of orphaned children and witches we have lone women hastening breathlessly on errands of mercy or information. There is, for example, Mary Slocumb of North Carolina, who dreamed that her husband was lying dead in battle. She “rose in the night, saddled her horse and rode at full gallop.” When she gets to the battlefield she finds a wounded man wrapped in her husband’s cloak, but it turns out to be another man, whom she nurses. She finds her husband unharmed. After working with the wounded for a day, “In the middle of the night she again mounted and started for home, declining the offer to send an escort with her . . . This resolute woman thus rode alone, in the night, through a wild, unsettled country, a distance—going and returning—of a hundred and twenty-five miles, and that in less than forty hours, and without any interval of rest!”

Or there is the tale of Dicey Langston, who, in order to give warning of British troop movements to her brother’s detachment, left

her home alone, by stealth, and at the dead hour of night. Many miles were to be traversed, and the road lay through woods, and crossed marshes and creeks where the conveniences of bridges and foot-logs were wanting. She walked rapidly on, heedless of slight difficulties; but her heart almost failed her when she came to the banks of the Tyger—a deep and rapid stream, rendered more dangerous by the rains that had lately fallen. But the thought of personal danger weighed not with her . . . . The hoarse rush of the waters, which were up to her neck—the blackness of the night—the utter solitude around her—the uncertainty lest the next step should ingulph her past help, confused her . . . But the energy of a resolute will, under the care of Providence, sustained her.

These tales demand deconstruction. Of course we need to proceed with caution, recognizing that they are nineteenth-century tales, not eighteenth-century artifacts. The analogy to the Grimm tales is surely not be accidental; as Hermann Rebel and Peter Taylor have recently pointed out, the Grimm tales come from the same region that furnished the Hessian soldiers and were developed at the same time. The Grimm tales—especially those that focus on impoverished children thrust out prematurely to seek their fortunes and on sons deprived of their birthright—resonate with themes that link them to the American Revolution. Ellet’s versions were constructed in the 1840s, and the manner of their retelling expresses nineteenth-century romanticism and the limitations of professional historians of her generation at least as much as it does eighteenth-century experience. Still, the themes that her informants kept transmitting to her are rich ones for our understanding of how at least some ordinary women perceived their experience. These women understood that they had been victims; they claimed for themselves fortitude, decency, and heroism. Ellet’s informants located their action in the interstices of the great public set pieces of the historical drama, but they did not underestimate their value.

Ellet’s revision of the narrative of the Revolution will not satisfy the twentieth-century historian seeking an account of the Revolution that embeds women’s roles and experiences deeply into both narrative and analysis. Ellet ignored themes that we now find indispensable: major questions of strategy and tactics, of internal and international politics, of class relations, of the social dynamics of the army. The actors on Ellet’s stage are an unbalanced assortment of American officers, who are made to stand for the entire armed forces, and individual civilian women, who stand only for themselves.

But if we cannot rely on Ellet, neither can we rely on currently popular narratives of the war to tell us about the experiences of both men and women, whether they were black or white. Although the last decade has seen an outpouring of new specialized scholarship on the distinctive experiences of women, the main lines of general analysis have not changed recognizably. The women of the revolutionary era remain becalmed in the E208 section of our libraries, wringing their hands like the White Queen in Through the Looking Glass, suffering gracefully in otherwise admirable books of otherwise distinguished historians.

For example, virtually the only woman we meet in Robert Middlekauff’s magisterial The Glorious Cause (the first volume in the new Oxford History of the United States), is Sarah Hodgkins of Ipswich, Massachusetts, who assures her husband of her love through the strenuous years of war, and, when his battlefield is close enough, takes in his washing and sends his clean clothes back in a packet. In Charles Royster’s prize-winning A Revolutionary People at War, we encounter only two women—Janet Montgomery, who spends the years after her husband’s death in battle burnishing his reputation to a fine gloss, and poor Faithy Trumbull Huntington, who is so unhinged by her view of the battlefield at Bunker Hill (as well she might have been) that she is driven to suicide.

Yet the ingredients—both material and theoretical—for an analysis that recognizes the role of gender in the Revolutionary War are now available. We know better than to discount the female experience as inherently marginal or trivial. We have gathered a considerable amount of information and know where to get more about the actions and responses of women in the prerevolutionary political crises and in the war itself. Although sex remains a biological given, gender—the learned sense of self, the social relations between the sexes—is now well understood to be a social construction. We understand better the paradoxical quality of Western ideas about women, which, at least since the Middle Ages, have stressed both that women were weak and should be ruled by men and that women were more disorderly, more lustful, and yet less predictable than men. We are ready to ask whether and how the social relations of the sexes were renegotiated in the crucible of Revolution.

Like all revolutions, the American Revolution had a double agenda. Patriots sought to exclude the British from power: this task was essentially physical and military. Patriots also sought to accomplish a radical psychological and intellectual transformation: “the principles, morals and manners of our citizens” Benjamin Rush argued, would need to change to be congruent with “our new forms of government.” As Cynthia Enloe has remarked, a successful revolutionary movement establishes new definitions of “what is valued, what is scorned, what is feared, and what is believed to enhance safety and security.”

In America this transformation involved a sharp attack on social hierarchies and a reconstruction of family relationships, especially between husbands and wives and between parents and children. Military resistance was enough for rebellion; it was the transformation of values—which received classic expression in Thomas Paine’s Common Sense—that defined the Revolution. Both tasks were intertwined, and both tasks—resistance and redefinition—involved women as supporters and as adversaries far more than we have understood.

If the army is described and analyzed solely from the vantage point of central command, the women and children will be invisible. To view it from the vantage point of the foot soldier and the thousands of women who followed the troops is to emphasize the marginality of support services for both armies, and the penetrability of the armies by civilians, especially women and children. From the women’s perspective, the American army looks far less professional, far more disorganized, than it appears to be in most monographs and synthesizing accounts of the war of the Revolution.

Women were drawn into the task of direct military resistance to a far greater extent than we have appreciated. Along with the French Revolution, the American Revolution was the last of the early modern wars. As they had since the sixteenth century, thousands of women and children traveled with the armies, functioning as nurses, laundresses, and cooks. Like the emblematic Molly Pitcher, they made themselves useful where they could—hauling water for teams that fired cannon, bringing food to men under fire. In British practice, with which the colonists had become familiar during the Seven Years War, each company had its own allocation of women, usually but not always soldiers’ wives and occasionally mothers; when the British sailed their women sailed with them. This role remains unstudied; we still depend on Walter Hart Blumenthal’s 1952 account. He reports that in the original complement of eight regiments that the British sent to put down the American rebellion, each regiment had 677 men and 60 women, a ratio of approximately 1 to 10.

Patriots were skeptical about giving women official status in the army; Washington objected to a fixed quota of women. But the women followed nevertheless, apparently for much the same reasons as the British and German women did. By the end of the war, Washington’s General Orders established a ratio of one woman for every 15 men in a regiment. Extrapolating from this figure, Linda Grant De Pauw estimates that in the course of the war some “20,000 individual women served as women of the army on the American side.” Some, no doubt, came for a taste of adventure. Generals’ wives, like Martha Washington and Catherine Greene, took their right to follow as a matter of course and spent the winters of Valley Forge and Morristown with their husbands. But by far most women who followed the armies were impoverished. Wives and children who had no means of support when their husbands and fathers were drawn into service—whether by enthusiasm or in the expectation of bounties—followed after and cared for their own men, earning their subsistence by nursing, cooking, and washing for the troops in an era when hospitals were marginal and the offices of quartermaster and commissary were inadequately run.

The women of the army made Washington uncomfortable. He had good reason to regard these women with skepticism. Although they processed food and supplies by cooking and cleaning, they were also a drain on these supplies in an army that never had enough. Even the most respectable women represented something of a moral challenge; by embodying an alternate loyalty to family or lover, they could discourage reenlistment or even encourage desertion in order to respond to private emotional claims. They were a steady reminder to men that there was a world other than the controlled one of the camp; desertion was high throughout the war and no general needed anyone who might encourage it further. Most importantly, perhaps, the women of the army were disorderly women, who could not be controlled by the usual military devices and who were invariably suspected of theft and spying for the enemy. As a result, Washington was constantly issuing contradictory orders. Sometimes the women of the army were to ride in the wagons so as not to slow down the troops; at other times they were to walk so as not to take up valuable space in the wagons. But always they were there, and Washington knew they could not be expelled. These women drew rations in the American army; they brought children with them, who drew half rations. American regulations took care to insist that “suckling babes” could draw no rations at all, since obviously they couldn’t eat.

It is true that cooking, laundering, and nursing were female skills; the women of the army were doing in a military context what they had once done in a domestic one. But we ought not discount these services for that reason or visualize them as taking place in a context of softness and luxury. “One observer of American troops . . . attributed their ragged and unkempt bearing to the lack of enough women to do their washing and mending; the Americans, not being used to doing things of this sort, choose rather to let their linen, etc., rot upon their backs than to be at the trouble of cleaning ’em themselves.” Washington was particularly shocked at the demeanor of the troops at Bunker Hill, some of whom apparently were so sure that washing clothes was women’s work that “they wore what they had until it crusted over and fell apart.” A friend of Mercy Otis Warren’s described the women who followed the Hessians after the surrender of Burgoyne: “great numbers of women, who seemed to be the beasts of burthen, having a bushel basket on their back, by which they were bent double, the contents seemed to be Pots and Kettles, various sorts of Furniture, children peeping thro’ gridirons and other utensils, some very young Infants who were born on the road, the women bare feet, cloathd in dirty raggs, such effluvia filled the air while they were passing, had they not been smoaking all the time, I should have been apprehensive of being contaminated by them . . . . “ Susannah Rowson’s fictional Charlotte Temple, at the end of her rope, is bitterly advised to “go to the barracks and wash for a morsel of bread; wash and mend the soldiers’ cloaths, and cook their victuals . . . work hard and eat little.”

Women who served such troops were performing tasks of the utmost necessity if the army were to continue functioning. John Shy has remarked that the relative absence of women among American troops put Americans at a disadvantage in relation to the British; women maintained “some semblance of orderliness.” They did not live in gentle surroundings in either army, and the conditions of their lives were not pleasant. Although they were impoverished, they were not inarticulate. The most touching account of Yorktown I know is furnished by Sarah Osborn, who cooked for Washington’s troops and delivered food to them under fire because, as she told Washington himself, “it was not fair that the poor fellows should fight and go hungrey too.” At the end she watched the British soldiers stack their arms and “go off to await their destiny.”

Women had been embedded in the military aspects of the war against England, but their roles were politically invisible. Americans literally lacked a language to describe what was before their eyes. On the other hand, women were visible, even central, to the Revolution and to the patriot effort to transform political culture. They were visible in at least three ways.

A dramatic feature of prerevolutionary political mobilization was consumer boycotts. These boycotts were central to the effort to change values, to undermine psychological as well as economic ties to England, and to draw a political people into political dialogue. Although consumer boycotts seem to have been devised by men, they were predicated on the support of women, both as consumers—who would make distinctions on what they purchased as between British imports and goods of domestic origin—and as manufacturers, who would voluntarily increase their level of household production. Without the assistance of “our wives,” conceded Christopher Gadsden, “’tis impossible to succeed.”

Women who had thought themselves excused from making political choices now found that they had to align themselves politically, even behind the walls of their own homes. As they decided how much spinning to do, whether to set their slaves to weaving homespun, or whether to drink tea or coffee, men and women devised a political ritual congruent with women’s understanding of their domestic roles and readily incorporated into their daily routines. [The loyalist Peter Oliver suspected that undermining of the boycott was also easily incorporated into daily routine: “The Ladies too were so zealous for the Good of their Country, that they agreed to drink no Tea, except the Stock of it which they had by them; or in the Case of Sickness. Indeed, they were cautious enough to lay in large Stocks before they promised; & they could be sick just as suited their Convenience or Inclination.”]

The boycotts were an occasion for instruction in collective political behavior, formalized by the signing of petitions and manifestos. In 1767, both men and women signed the Association, promising not to import dutied items. Five years later, when the Boston Committee of Correspondence circulated the Solemn League and Covenant establishing another boycott of British goods, they demanded that both men and women sign. Collective petitions would serve women as their most usable political device deep into the nineteenth century.

After the war, control of their consumption patterns would remain the most effective political weapon in women’s small political arsenal. Consumption boycotts were used during the Quasi-War in the 1790s and persisted into the nineteenth century; when women’s abolitionist societies searched in the 1830s and 1840s for a strategy to bring pressure on the slave economy, a boycott of slave-made goods would be to them an obvious answer.

Nowhere can the dependence of rebellion on the transformation of values be seen more clearly than in the continuing struggle for recruitment into the army or militia. The draft never worked automatically; ways had to be devised to co-opt men, and this co-optation had to take place against men’s own inertia and lack of enthusiasm for placing themselves at risk. One explicit mode of deflecting resistance was the offering of bounties in money or in land. Another was the psychological and legal pressures of milita training. In every state except Pennsylvania, militias inscribed every able-bodied free white man in their rolls, and drew those men together in the public exercises of training day. There was no counterpart for women of a training day as a bonding experience, which linked men to each other, to the local community, and at the same time to the state.

Training day underscored men’s and women’s different political roles; military training was a male ritual that excluded women. In turn, women castigated it as an arena for antisocial behavior. When peacetime drill turned into actual war, women would logically complain that they had been placed at risk without their consent. No one asked women if they thought the war worth the cost, yet women faced intrusion, violence, and rape. Religiously believing women were deeply skeptical of a military culture that encouraged drink as indispensable to the display of courage and was unperturbed by those who broke the third commandment (against swearing).

In this context, patriots needed to find an alternative to women’s traditional skepticism and resistance to mobilization. It is not yet clear whether the primary energy for this alternative came from men seeking to deflect women’s resistance or from those women who wished to define for themselves a modern political role in which they could demonstrate their own voluntary commitment to the Revolution. In either case, the alternative role involved sending one’s sons and husband to battle. The Pennsylvania Evening Post offered the model of “an elderly grandmother of Elizabethtown, New Jersey” in 1776.

My children, I have a few words to say to you, you are going out in a just cause, to fight for the rights and liberties of your country; you have my blessings . . . Let me beg of you . . . that if you fall, it may be like men; and that your wounds may not be in your back parts.

Ellet’s books were replete with examples equally hard to take literally. “A lady of New Jersey” calls after her parting husband: “Remember to do your duty! I would rather hear that you were left a corpse on the field than that you had played the part of a coward!”

Women who thrust their men to battle were displaying a distinctive form of patriotism. They had been mobilized by the state to mobilize their men; they were part of the moral resources of the total society. Sending men to war was in part their expression of surrogate enlistment in a society in which women did not fight. This was their way of shaping the construction of the military community. They were shaming their men into serving the interests of the state; indeed shaming would become in the future the standard role of civilian women in time of war. The pattern is far older than the American Revolution, but it was strengthened during that war and further enlarged during the French Revolution. It would reach its apogee in England during World War I, when women handed out white feathers to men who walked the streets of London in civilian dress and when a modern state maintained a mass war with volunteers alone for two long years.

The third way in which women transformed what was valued and what was scorned involved crowd behavior that was both disorderly and ritualized—sometimes at one and the same time. Working women, who spent much of their lives on the streets as market women or shopkeepers, surely were part of the crowds of the 1760s and 1770s. Women formed part of funeral processions; they were present in the great public funerals for the victims of the Boston Massacre and for the martyred child Christopher Seider. (Mercy Otis Warren helped solidify Seider’s martyred status by her play The Adulateur.)

Women also invented their own public rituals. Most noteworthy of these was the effort of Hannah Bostwick McDougall in New York in April 1770. When her husband the patriot Alexander McDougall was arrested for publishing a seditious broadside, his wife “led a parade of ladies from Chapel Street to the jail, entertaining them later at her home.” As part of the campaign to make him into the American Wilkes, “45 virgins went in procession to pay their respects,” and McDougall “entertained them with tea, cakes, chocolate, and conversation.”

Better known is the house-to-house campaign of the patriot women of Philadelphia, led by Esther Reed and Deborah Franklin Bache, to raise money for Washington’s soldiers and to get women of other states to do the same, accompanied by an explicit political broadside and by intimidating fund-raising. “I fancy they raised a considerable sum by this extorted contribution,” sneered Quaker loyalist Anna Rawle, “some giving solely against their inclinations thro’ fear of what might happen if they refused.”

Bringing ritual resistance to Britain out of the household and into the streets shaded into violence. During the war, boycotts occasionally escalated into what the French would call taxation populaire, such as the intimidation of the “eminent, wealthy, stingy” Thomas Boylston in Boston for hoarding coffee or the intimidation of Peter Mesier by Westchester women. The most violent act of resistance we know is perhaps that of the New York woman who was the first to be accused of incendiarism in the Great Fire when the British entered the city in 1776. She received her eulogy from Edmund Burke on the floor of the House of Commons:

. . . still is not that continent conquered; witness the behaviour of one miserable woman, who with her single arm did that, which an army of a hundred thousand men could not do—arrested your progress, in the moment of your success. This miserable being was found in a cellar, with her visage besmeared and smutted over, with every mark of rage, despair, resolution, and the most exalted heroism, buried in combustibles, in order to fire New-York, and perish in its ashes;—she was brought forth, and knowing that she would be condemned to die, upon being asked her purpose, said, “to fire the city!” and was determined to omit no opportunity of doing what her country called for. Her train was laid and fired; and it is worthy of your attention, how Providence was pleased to make use of those humble means to serve the American cause, when open force was used in vain.

When Elizabeth Ellet created the first history of women during the American Revolution, she recorded the way middle-class survivors and their descendants remembered their experience. Writing of women, Ellet confirmed their victimization, their decency, and their respect for ceremony and propriety in the midst of horror. She did not want to hear, nor did her informants wish to recover for her, the record of women’s presence in violent crowds, their thefts, their spying. She offered posterity women of sensitivity and the sentiment that her own Romantic culture required of females; she blotted disorderly women from memory.

Boycotting imports, shaming men into service, disorderly demonstration—all were ways in which women obviously entered the new political community created by the Revolution. It was less apparent what that entrance might mean. There followed a struggle to define women’s political role in a modern republic. The classic roles of women in wartime were two: both had been named by the Greeks, both positioned women as critics of war. Antigone and Cassandra are both outsiders, and therefore are less subject than men to ambivalence about doing their share or abandoning their comrades; they are free to concentrate on the price rather than the promise of war. While understanding that she cannot affect the outcome of battle, Antigone, who confronts Creon with the demand that her brothers’ bodies be buried, claims the power to set ethical limits on what men do in war. Named for the woman who foresees the tragic end of the Trojan War, Cassandra expresses generalized anxiety and criticism.

In America an evangelical version of Cassandra flourished. Many, perhaps most, women were unambivalently critical of the war and offered their criticism in religious terms. In 1787, when the delegates to the Philadelphia Convention were stabilizing a revolutionary government and embodying their understanding of what the Revolution had meant in the Federal Constitution, there appeared the classic text of the alternate perspective: a pamphlet called “Women Invited to War.” The author defined herself as a “Daughter of America,” and addressed herself to the “worthy women, and honourable daughters of America.” She acknowledged that the war had been a “valiant . . . defense of life and liberty,” but discounted its ultimate significance. The real war, she argued, was not against England, or Shaysites, but against the Devil. Satan was “an enemy who has done more harm already, than all the armies of Britain ever will be able to do . . . we shall all be destroyed or brought into captivity, if the women as well as the men, do not oppose, resist, and fight against this destructive enemy.”

In a few pages the author had moved from the contemplation of women in war emergencies to the argument that women ought to conduct their wars according to defintions that were different from men’s; that the main tasks that faced the republic were spiritual rather than political, and that in these spiritual tasks women could take the lead, indeed that they had a special responsibility to display “mourning and lamentation.”

In the aftermath of the revolutionary war, many women continued to define their civic obligations in this religious way; the way to save the city, argued the “Daughter of America,” was to purify one’s behavior and pray for the sins of the community. By the early nineteenth century, women flooded into the dissenting churches of the Second Great Awakening, bringing their husbands and children with them, and asserting that their claim to relgious salvation made possible new forms of assertive behavior—criticizing sinful conduct of their friends and neighbors, sometimes traveling to new communities and establishing new schools, sometimes widening in a major way the scope of the books they read. Churches also provided the context for women’s benevolent activity. Despairing that secular politics would clear up the shattered debris of the war, religious women organized societies for the support of widows and orphans in an heretofore unparalleled collective endeavor. If women were to be invited to war, they would join their own war and on their own terms.

To define the woman citizen as Cassandra is to constrain her permanently to the role of outsider as well as critic; at her worst Cassandra simply whines. The traditional role was clearly not enough to meet the rising expectations generated by war. The role of Antigone, with its claim that women might judge men was perhaps more appealing, but it was best suited to exhausting moments of dramatic moral confrontation, and Antigone cannot make her claim effective until she is dead. Moreover, neither solution (certainly not Cassandra in her updated evangelical form) entered directly into dialogue with the problem of bringing the Revolution to political closure. Both maintained the classic dichotomy in which men were the defenders of the state and women were the protected. Neither addressed the task of devising a new relationship between the individual and the state, or of forcing the state to be responsive to public opinion in a rigorous and regular way. It did not address the role of the woman as citizen of a republic; for that a secular political solution was required.

Between 1775 and 1777, statutory language moved from the term subject to inhabitant, member, and, finally, citizen. By 1776 patriots were prepared to say that all loyal inhabitants, men and women, were citizens of the new republic, no longer subjects of the king. But the word citizen still carried overtones inherited from antiquity and the Renaissance, when the citizen made the city possible by taking up arms on its behalf. In this way of reasoning, the male citizen “exposes his life in defense of the state and at the same time ensures that the decision to expose it can not be taken without him; it is the possession of arms which makes a man a full citizen . . . . “ This mode of thinking, this way of relating men to the state, had no room in it for women except as something to be avoided. [The principal section on women and the state in Machiavelli’s Discourses is entitled “How a State Falls Because of Women.”] Thus, as Charles Royster reports, “The first anniversary of the Declaration of Independence was celebrated with the toast ’May only those Americans enjoy freedom who are ready to die for its defence.’ “ To be free, required a man to risk death. In a formulation like this one, the connection to the republic of male patriots—who could enlist—was immediate. The connection of women, however patriotic they might feel themselves to be, was remote.

Many aspects of American political culture reinforced the genderspecific character of citizenship. First, and most obvious, men were linked to the republic by military service. Military service performed by the women of the army was not understood to have a political component. Second, men were linked to the republic by the political ritual of suffrage, itself an expression of the traditional link between political voice and ownership of property deeply embedded in Lockean political theory. The feme covert, who normally did not control the disposition of family property, was equally if not more vulnerable to direction and manipulation by her husband or guardian. Women of the laboring poor were, of course, particularly vulnerable. Like all married women they were legally dependent on their husbands; as working people the range of economic opportunities open to them was severely restricted. Apprenticeship contracts, for example, reveal that cities often offered a wide range of artisanal occupations to boys but limited girls to housekeeping and occasional training as a skilled seamstress. Almshouse records display a steady pattern: most residents were women and their children; most “outwork” was taken by women. Their lack of marketable skills must have smoothed the path to prostitution for the destitute. The material dependency of women was well established in the early republic. Indeed, the assumption that women as a class were dependent was so well established that individual women who were not materially dependent [for example, wealthy widows or never-married women] were treated as though they were dependent in political theory and in practice.

Finally, men were linked to the revolutionary republic psychologically, by their understanding of self, honor, and shame. These psychological connections were gender specific and therefore unavailable to women. Thus in his shrewd analysis of the psychological prerequisite for rebellion, Tom Paine linked independence from the empire to the natural independence of the grown son. The image captured the common sense of the matter for a wide range of American men, who made Common Sense their manifesto. Charles Royster has brilliantly described the psychological tension experienced by army officers caught in the web of idealistic expectations for fame and honor that were embedded in the “ideals of 1775.”

The promise of fame was positive reinforcement for physical courage. The army had negative reinforcements as well. For cowardice there were courts-martial and dismissal from service. There was also humiliation, which might take the form of “being marched out of camp wearing a dress, with soldiers throwing dung at him.” Manliness and honor were thus sharply and ritually contrasted with effeminacy and dishonor. It is not accidental that dueling entered American practice during the Revolution. Usually “British and French aristocrats” are blamed for its introduction but that does not explain American receptivity; the duel fit well with officers’ need to define their valor and to respond to their anxieties about shame.

All these formulations of citizenship and civic relations in a republic were tightly linked to men and manhood; it was men who offered military service, men who sought honor, men who dueled in its defense. In a triumphant feat of circular definition, it was understood by all that women could not offer military service—not even the “women of the army” were understood to do so. Nor could women pledge their honor in defense of the republic, since honor, like fame, was psychologically male. The language of citizenship for women had to be freshly devised.

With virtually no aid from political theory, the revolutionary generation addressed the conundrum. Women were assisted in their effort to refine the concept of the woman citizen by changes in male understanding of the role. “The people” of revolutionary broadsides had clearly been meant to include a broader sector of the population than had been meant by the citizenry of Renaissance Florence; how much more inclusive American citizenship ought to be was under negotiation. It seemed obvious that it had to include more than those who actually took up arms. Gradually, as James H. Kettner has explained, allegiance (as demonstrated by one’s physical presence and also emotional commitment) came to be given equal weight with military service. An allegiance defined by location and volition was an allegiance in which women could join. As this latter sort of citizen, women could be part of the political community, unambivalently joining in boycotts, fund-raising, street demonstrations, and the signing of collective statements.

But the nature of citizenship remained gendered. Behind it still lurked old republican assumptions, beginning with the obvious one that men’s citizenship included a military component and women’s did not. The classical republican view of the world had been bipolar at its core, setting reason against the passions, virtue against the vagaries of fortune, restraint against indulgence, manliness against effeminacy. The first item in each of these pairs was understood to be a male attribute. The second was understood to be characteristic of women’s nature; when displayed by men it was evidence of defeat and failure. The new language of independence and individual choice (which would be called liberal) welcomed women’s citizenship; the old language of republicanism deeply distrusted it.

Between 1770 and 1800 many writers, both male and female, articulated a new understanding of the civic role of women in a republic that drew on some old ingredients but rearranged them and added new ones, to create a gendered definition of citizenship, which attempted (with partial success) to resolve these polarities. The new formulation also sought to provide an image of female citizenship alternative to the passivity of Cassandra or the crisis-specificity of Antigone. The new formulation had two major—and related—elements. The first, expressed with extraordinary clarity by Judith Sargent Murray in America and Mary Wollstonecraft in England, stressed women’s native “capability” and competence and offered them as preconditions of citizenships. “How can a being be generous who has nothing of its own? or virtuous who is not free?” asked Wollstonecraft. Murray offered model women who sustained themselves by their own efforts, including one who ran her own farm.

With women understood to be competent, rational, and independent beings, it finally became possible to attack directly the classical allocation of civic virtue to men and of unsteadiness, fortuna, to women. The mode of attack implicitly undermined yet another ingredient of the classical republican view of the world: its cyclical vision of historical time.

Theorists of the Revolution were sharply aware of the danger of the epigone: the generation that cannot replicate the high accomplishments of its fathers. Both political theory and common sense taught that history was an endless cycle of accomplishment and degeneration; the Revolution had been intended to stop time and break the traditional historical cycle. But the revolutionary generation had been specific to its own time; it had developed out of experience with British tyranny and the exigencies of war. When the war was over, the leading Tories gone with the British, what was to prevent history from repeating itself? The problem was one every revolution and every successful social movement faces, made even more urgent by inherited political theory that seemed to assure disaster.

By claiming civic virtue for themselves, women undermined the classical polarities. Their new formulation of citizenship reconstructed gender relations, politicizing women’s traditional roles and turning women into monitors of the political behavior of their lovers, husbands, and children. The formulation assumed for women the task of stopping the historical cycle of achievement followed by inevitable degeneration; women would keep the republic virtuous by maintaining the boundaries of the political community. Women undertook to monitor the political behavior of their lovers: “notwithstanding your worth,” wrote Cornelia Clinton to Citizen Edmond Genet [whom she would later marry] during his troubled mission to persuade Washington to abandon neutrality, “I do not think I could have been attached to you had you been anything but a Republican support that character to the end as you have begun, and let what may happen . . . . “ Mercy Otis Warren adamantly cautioned her son Winslow against reading Lord Chesterfield, advice congruent with her steady belief that “luxurious vices . . . have frequently corrupted, distracted and ruined the best constituted republics.” Thus Lockean child rearing was given a political twist; the bourgeois virtues of autonomy and self-reliance were given extra resonance by the revolutionary experience.

It was in her role as mother that the republican woman entered historical time and republican political theory, implicitly promising to arrest the cycle of inevitable decay by guaranteeing the virtue of subsequent generations, that virtue which alone could sustain the republic, guarding the revolutionary generation against the epigone.

Let us then figure to ourselves the accomplished woman, surrounded by a sprightly band, from the babe that imbibes the nutritive fluid, to the generous youth just ripening into manhood, and the lovely virgin, blest with a miniature of maternal excellence. Let us contemplate the mother distributing the mental nourishment to the fond smiling circle . . . See, under her cultivating hand, reason assuming the reins of government, and knowledge increasing gradually to her beloved pupils . . . . the Genius of Liberty hovers triumphant over the glorious scene; Fame, with her golden trump, spreads wide the well-earned honours of the fair . . . .

As the comments of the Columbia commencement speaker suggest, the construction of the role of the woman of the republic marked a significant moment in the history of gender relations. What it felt like to be a man and what it felt like to be a woman had been placed under considerable stress by war and revolution; when the war was over it was easy to see that it had set in motion a revised construction of gender roles. Wars that are not fought by professional armies almost always force a renegotiation of sex roles, if only because when one sex changes its patterns of behavior the other sex cannot help but respond. In this the American Revolution was not distinctive. The Revolution does seem to have been distinctive, however, in the permanence of the newly negotiated roles, which took on lives of their own, infusing themselves into Americans’ understanding of appropriate behavior for men and for woman deep into the nineteenth and even twentieth centuries.

Revolutionary ideology had no place in it for the reconstruction of women’s roles. But these roles could not help but change under the stress of necessity and in response to changes in men’s behavior. Dependence and independence were connected in disconcerting ways. For example, the men of the army were dependent on the services of the women of the army, much as the former would have liked to deny the existence of the latter. And, paradoxically, although men were “defenders” and women “protected” in wartime, the man who left his wife or mother to “protect” her by joining the army might actually place her at greater physical risk. Even those most resistant to changed roles could not help but respond to the changed reality of a community in which troops were quartered or from which supplies were commandeered. Women’s survival strategies were necessarily different from those of men.

It ought not surprise us that women would also develop different understandings of their relationship to the state. In the years of the early republic, middle- and upper-class women gradually asserted a role for themselves in the republic that stressed their worthiness of the lives that had been risked for their safety; their service in maintaining morals and ethical values; and their claim to judge fathers, husbands, and sons by the extent to which these men lived up to the standards of republican virtue, which they professed. Seizing the concept of civic virtue, women made it their own, claiming for themselves the responsibility of committing the next generation to republicanism and civic virtue and succeeding so well that by the antebellum years it would be thought to be a distinctively female concept and its older association with men largely forgotten. Virtue would become for women what honor was for men: a private psychological stance laden with political overtones.

Those who did most to construct the ideology of republican womanhood—like Judith Sargent Murray and Benjamin Rush—had reflected revolutionary experience authentically, but also selectively. They drew on revolutionary ideology and experience, emphasizing victimization, pride, decency, maintenance of ritual, and of self-respect. But they denied the most frightening elements of that experience. There was no room in the new construction for the disorderly women who had emptied their piss pots on stamp tax agents, intimidated hoarders, or marched with Washington and Greene. There was no room for the women who had explicitly denied the decency and appropriateness of the war itself. There was no room for the women who had despaired and who had contributed to a war-weary desire for peace at any price in 1779–81. There was no room for the women who had fled with the Tories; no room, in short, for women who did not fit the reconstructed expectations. Denial of disorder was probably connected to the institutionalization of the Revolution in the federal republic. The women of the army were denied as the Shaysites were denied; to honor and mythologize them would have been to honor and to mythologize the most disconcerting and threatening aspects of rebellion.

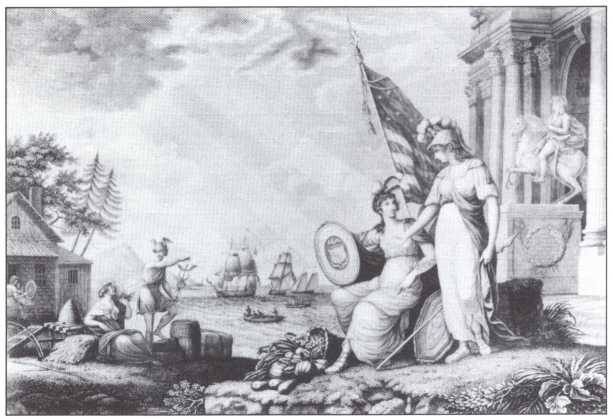

In announcing her certainty that the essential differences between the sexes lay in the realm of feeling and sentiment, Elizabeth Ellet had offered not only a different memory of the Revolution but also a selective one that reflected the selective memories of her informants. Yet Elizabeth Ellet was no naif. She understood that to place gender at the narrative center of the revolutionary experience would require a major shift of perspective and would introduce complexity and ambivalence into issues previously assumed to be one dimensional. In painting, an analogy would be the shift from the directness and simplicity of John Trumbull’s great painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence that hangs in the Capitol Rotunda—a painting that must be seen in the same way by each pair of eyes, depicting one species, using one vanishing point—to the doubled vision of modern painting like Henri Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy, an unsettling painting because, as Arthur Danto has explained, we see at the same moment, the gypsy from the perspective of the lion and also see the lion, foreshortened, looking down, from the perspective of the gypsy. When we write, at last, an authentic, holistic history of the Revolution, it will be no easier to read than Rousseau or Picasso are to view. The new narrative will be disconcerting; its author will have the ability to render multiple perspectives simultaneously.

The new narrative will provide a more rigorous investigation of the sexual division of labor prevalent in America in the second half of the eighteenth century; it will provide a more rigorous investigation of the impact of civil unrest, war, and a changing global economy on that labor system. The new narrative will make room for the women who lived in the interstices of institutions that we once understood as wholly segregated by gender: the women tavern keepers who provided the locales for political meetings, the thousands of orderly and disorderly women on whom the army was dependent for essentials of life. The new narrative will imply a more precise account of the social relations of the sexes in the early republic, a precision that in turn will make it possible for us to develop a more nuanced understanding of the extent to which Victorian social relations were a response to what had preceded them.

In the new narrative, the Revolution will be understood to be more deeply radical than we have heretofore perceived it because its shock reached into the deepest and most private human relations, jarring not only the hierarchical relationships between ruler and ruled, between elite and yeoman, between slave and free, but also between men and women, husbands and wives, mothers and children. But the Revolution will also be understood to be more deeply conservative than we have understood, purchasing political stability at the price of backing away from the implications of the sexual politics implied in its own manifestos, just as it backed away from the implications of its principles for changed race relations. It may not be too much to say that the price of stabilizing the Revolution was an adamant refusal to pursue its implications for race relations and for the relations of gender, leaving to subsequent generations to accomplish what the revolutionary generation had not. [It might also be remarked that, by contrast, French revolutionaries did admit to debate the possibility of major change in the social relations of the sexes, as shown in working-class women’s seizure of power in the October Days, in divorce legislation, in admission of women to the oath of loyalty and citizenship, and in the programs of Jacobin societies of revolutionary republican women; but it could also be argued that thus entertaining the woman question was severely destabilizing and contributed to the disruption of the republic in 1793–95.]

In the end, most men and women were probably less conscious of changed relationships than of simple relief that they had survived. When the war was over, Mercy Otis Warren wrote a play about two women caught in a revolutionary war in which she placed herself as heroine. Her message was framed in terms of the contrasting experience of two women, but its burden surely was meant to apply to both sexes. The Ladies of Castille is about two women of contrasting temperaments caught up in a revolutionary civil war; it provided the heroic imagery by which Americans would prefer, from that day to this, to embed their Revolution. The soft and delicate Louisa, who introduces herself with the words, “I wander wilder’d and alone Like some poor banish’d fugitive . . . I yield to grief” is contrasted with the determined Maria, who announces in her opening that she scorns to live “upon ignoble terms.” The message of The Ladies of Castile is simple and obvious: the Louisas of the world do not survive revolutions; the Marias—who take political positions, make their own judgment of the contending sides, risk their own lives—emerge stronger and in control. Those who like Louisa, ignore politics, do so only at great risk. It was the Marias, whose souls grew strong by resistance, who took gritty political positions, who survive and flourish. “A soul, inspir’d by freedom’s genial warmth,” says Maria, “Expands—grows firm, and by resistance, strong.”